Summary contributed by our researcher Victoria Heath (@victoria_heath7). She’s also a Communications Manager at Creative Commons.

*Authors of full paper & link at the bottom

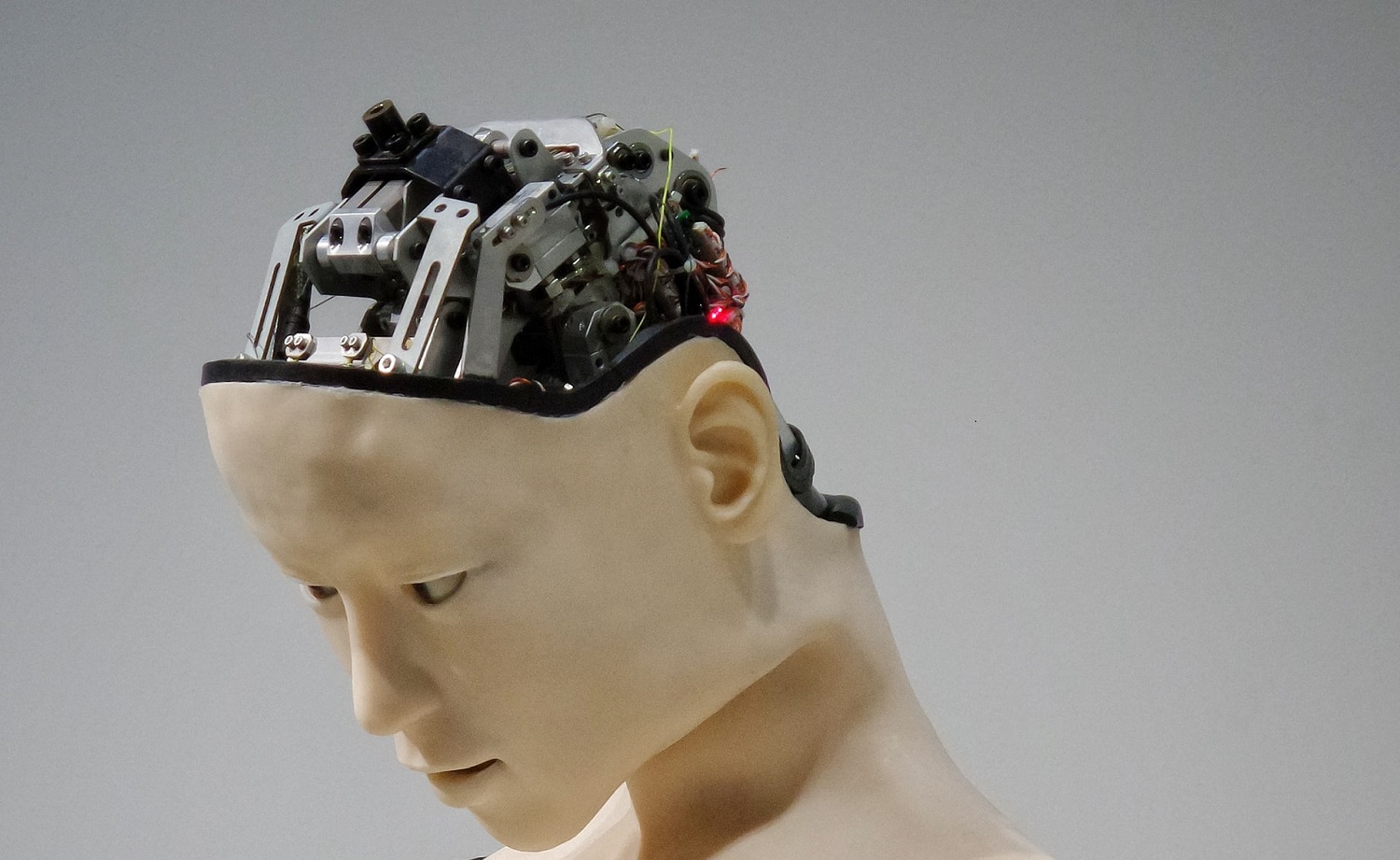

Overview: Robots and other artificially intelligent machines are often depicted as white. Search “robot” in Google Images and you’ll notice it immediately. This paper examines “how the ideology of race shapes connections and portrayals of AI”, contributing to an increasing number of studies and books looking at the connections between race and technology.

Intro

Robots and artificially intelligent machines are often depicted as white. Type in “robot” in Google Images and you’ll notice it immediately. This often unnoticed phenomenon is problematic and an example of how technology can be racialized. Authors Stephen Cave and Kanta Dihal from the University of Cambridge explain, “intelligent machines are predominately conceived and portrayed as White. We argue that this Whiteness both illuminates particularities of what (Anglophone Western) society hopes for and fears from these machines, and situates these affects within long-standing ideological structures that relate race and technology.”

In this paper, the authors examine “how the ideology of race shapes connections and portrayals of artificial intelligence (AI),” contributing to an increasing number of studies and books looking at the connections between race and technology (e.g. Safiya Noble’s Algorithms of Oppression). Their discussion is informed and framed by the philosophy of race and critical race theory, relying on Black feminist theories and work in Whiteness studies. More specifically, they utilize the “white racial frame” developed by Joe R. Feagin (2006) to examine representations of AI (e.g. white robots). By drawing attention to the “the operation of Whiteness” in technology, which is often normalized and made invisible, we can expose the “myth of colour-blindness” that is prevalent in tech culture that prevents “serious interrogation of racial framing” in technology.

The authors offer three interpretations of the Whiteness of AI: 1) normalization of Whiteness in the Anglophone West, 2) the White racial frame primarily ascribes intelligence to White people, and 3) it allows for “a full erasure of people of color from the White utopian imaginary.”

Seeing the Whiteness of AI

Machines Can Be Racialized

The idea of a “racialized” machine or technology may seem counterintuitive (and make designers uncomfortable), but research shows that when humans are asked to define the race of a robot presented to them, they do so easily. According to Cave and Dihal, this is primarily due to the fact that machines (including robots) are often anthropomorphised. In our society, appearing more “human-like” means to have a race. This is not only achieved through the color of a robot, but also the name it’s given, the voice, dialect, and more.

This racialization has significant consequences. Research has shown that people may feel more comfortable with a machine if it has the same racial identity as them. Unfortunately, this has a flip-side: people often project prejudice onto machines too. In one study, after participants watched three videos depicting a female-gendered android that appeared Black, White, and East Asian, they were asked to provide commentary. The researchers found that “the valence of commentary was significantly more negative towards the Black robot than towards the White or Asian ones and that both the Asian and Black robots were subject to over twice as many dehumanizing comments as the White robot.” Further studies have shown that the patterns of bias, discrimination, and prejudice in human-to-human interactions also show up in human-to-robot interactions.

Whiteness as the Norm for Intelligent Machines

To illustrate how White is the norm for intelligent machines, the researchers look at four categories: real humanoid robots, virtual personal assistants, stock images of AI, and portrayals of AI in film and television.

One of the most obvious (and infamous) examples of a White humanoid robot is Sophia from Hanson Robotics, but there are other examples such as Kismet, Cindy Smart Doll, My Friend Cayla, and more. When it comes to chatbots and virtual assistants, it’s often the sociolinguistic markers that indicate if they are racialized as White. Mark Marino wrote in 2014 about the natural language processing program ELIZA (created in 1966), “it was “performing standard white middle-class English.” Today’s virtual assistants are an example of how designers often make conscious decisions to ascribe certain sociolinguistic characteristics to their technology depending on their target market, which historically (and perhaps still) skewed wealthy and White.

In regards to stock images of AI, particularly anthropomorphized robots, the dominance of white (and White) depictions is stark. This can be particularly problematic, as these images are utilized widely to illustrate this technology in the media which influences how society perceives it. Closely connected is the predominance of Whiteness of AI in film and television, examples include robots or voice assistants from the Terminator, RoboCop, Blade Runner, I, Robot, Ex Machina, Her, A Space Odyssey, and more. It’s only recently that we’ve begun to see more “diverse” racial depictions, such as in Westworld and Humans.

Understanding the Whiteness of AI

Whiteness Reproducing Whiteness

“In European and North American societies, Whiteness is normalized to an extent that renders it largely invisible,” write Cave and Dihal, and it “confers power and privilege.” This has led to other colors being racialized while white is considered “an absence of color” and in technology, the “default.” This has also led to what was referred to earlier as “color blindness,” which further normalizes Whiteness, marginalizes other racialized groups, and dismisses or ignores the real world impacts of technology on different groups of people.

Some explanations for the Whiteness of AI have rested on the idea that the normalization of Whiteness leads designers to almost unconsciously design a machine as White. However, that doesn’t explain why not all created entities are portrayed as White. Cave and Dihal point out that often in science fiction writing, for example, extraterrestrials are racialized as non-White, more specifically, East Asian. Petty-criminals are often portrayed as Afro-Caribbean. To the authors, this suggests that the racialization of AI is more a choice than an unconscious decision due to the aforementioned White racial frame.

AI and the Attributes of Whiteness

Building on the previous section, Cave and Dihal argue, “AI is predominantly racialized as White because it is deemed to possess attributes that this frame [White racial frame] imputes to White people.” Those attributes are: intelligence, professionalism, and power. “Throughout the history of Western thought,” they write, “intelligence has been associated with some humans more than others.” This strain of thought is what bolstered colonial and imperialist campaigns under the guise of “civilizing” other nations, ethnic groups, and races (summarized by Rudyard Kipling as the “the white man’s burden”) and attempts to “measure” the intellectual capabilities of different racial groups (e.g. IQ test). Thus, Cave and Dihal argue, “it is to be expected that when this culture [White, European] is asked to imagine an intelligent machine, it imagines a White machine.” Another important aspect is generality. Being generally intelligent is often attributed to White people, and seeing that “general artificial intelligence” is the primary aim of the AI field, it is not difficult to link these together. “To imagine a truly intelligent machine,” they write, “one with general intelligence is therefore to imagine a White machine.”

Historically, professional work (e.g. medicine, business, etc.) has also been deemed unsuitable for most people. People of color were (and still are) systematically excluded from entering these fields. In White European and North American mainstream culture, this has led to a warped perspective of who is a professional. When one imagines a doctor, it’s more often than not a White male. Thus, as AI systems are believed to be capable of professional work in the future, “to imagine a machine in a white-collar job is therefore to imagine a White machine.” Here, Cave and Dihal mention the issue of power as well. “Alongside the narrative that robots will make humans redundant,” they write,” an equally well-known narrative is that they will rise up and conquer us altogether.” Interestingly, those narratives, especially in science fiction, portray the rising robots as hyper-masculine, White machines. Why? They argue, “it is unimaginable to a White audience that they will be surpassed by machines that are Black.” Thus, for a White designer (or science fiction writer) to imagine these machines overpowering and supplanting humanity, they “imagine a White machine.”

White Utopia

Cave and Dihal’s final hypothesis regarding the Whiteness of AI is that this racialization “allows the White utopian imagination to fully exclude people of color.” AI is believed to eventually lead to a “life of ease” for most people. Historically, leisure was restricted to the wealthier class of society and often came at the expense of working-class women of color who conducted the necessary labour that allowed for that leisure—often remaining “invisible” themselves due to the “dirty” nature associated with their work. Thus, in the White utopian imaginary, write Cave and Dihal, people of color would be removed altogether, “even in the form of servants.” Further, this omission may even extend to all women. “Seen as a form of offspring, artificial intelligence offers a way for the White men to perpetuate his existence in a rationally optimal manner,” they write, “without the involvement of those he deems inferior.”

Conclusion and Implications

The racialization of AI as White can cause several representational harms. Cave and Dihal point out three in particular:

- Amplify existing racial prejudices by sustaining and mirroring discriminatory perceptions that the attributes discussed in the section above (i.e. intelligence, professionalism, and power) are only ascribed to White people.

- Exacerbate injustices by situating these machines “in a power hierarchy above currently marginalized groups, such as people of color.” This may exacerbate automation bias, in which the machines (racialized White) are trusted above that of the people oppressed by them.

- Distort society’s perception of the risks and benefits of AI. For instance, the conversation around the labour impacts of AI could be framed primarily about the risks/benefits posed to White middle-class men or white collar professionals, while ignoring other groups. This could lead to policy focusing more on protecting one group while ignoring more marginalized groups.

Cave and Dihal position this paper in a larger conversation and process called decolonizing AI, in which scholars aim to break down “the systems of oppression that arose with colonialism and have led to present injustices that AI threatens to perpetuate and exacerbate.” They hope by drawing attention to the Whiteness of AI, it can be denormalized, noticed, and raised for discussion.

Original paper by Stephen Cave and Kanta Dihal: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13347-020-00415-6