🔬 Original article by Sean McGregor, machine learning PhD and AI Incident Database lead.

The AI Incident Database launched publicly in November 2020 by the Partnership on AI as a dashboard of AI harms realized in the real world. Inspired by similar databases in the aviation industry, its change thesis is derived from the Santayana aphorism, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” As a new and rapidly expanding industry, AI lacks a formal history of its failures and harms were beginning to repeat. The AI Incident Database thus archives incidents detailing a passport image checker telling Asian people their eyes are closed, the gender biases of language models, and the death of a pedestrian from an autonomous car. Making these incidents discoverable to future AI developers reduces the likelihood of recurrence.

What Have We Learned?

Now with a large collection of AI incidents and a new incident taxonomy feature from the Center for Security and Emerging Technology, we have a sense of our history and two statistics are worth highlighting.

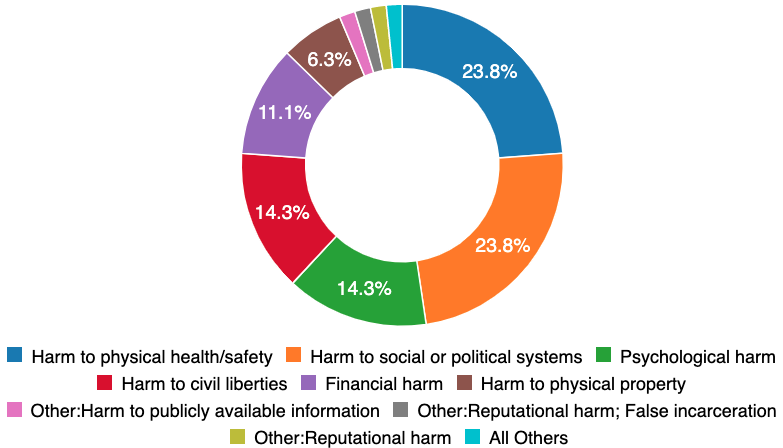

First, the harm types seen in the real world are highly varied. Existing societal processes (e.g., formal lab tests and independent certification) are prepared to respond to just the 24 percent of incidents related to physical health and safety. While an autonomous car poses obvious safety challenges, the harms to social and political systems, psychology, and civil liberties represent more than half of the incidents recorded to date. These incidents are likely either failures of imagination, or failures of representation. Let’s dial into “failures of imagination” with the observation that the majority of incidents are not distributed evenly across all demographics within the population.

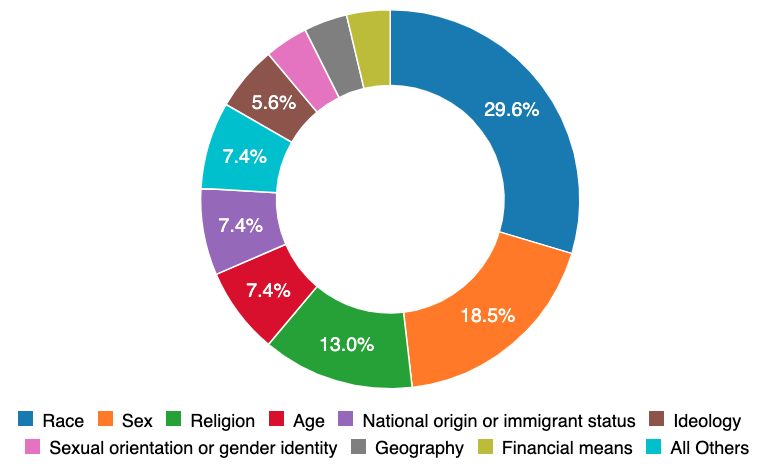

Of these “unevenly distributed” harms, 30 percent are distributed according to race and 19 percent according to sex. Many of these incidents could have been avoided without needing an example in the real world if the teams engineering the systems had more varied demographic identity.

So is representation a panacea to the harms of intelligent systems? No. Even were it possible to have all identities represented, there will still be incidents proving the limits of our collective imagination. For these “failures of imagination”, the AI Incident Database stands ready to ensure they can only happen once.

What is next?

If you compare the AI Incident Database to the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures database and the US Aviation Accident Database both have extensive software, processes, community integrations, and authorities accumulated through decades of private and public investment. Comparatively, the AI Incident Database is only at the beginning of its work ensuring AI is more socially beneficial. Three thematic areas are particularly important for building on the early successes of the AIID in its current form. These include,

1) Governance and Process. The AIID operates within a space lacking established and broadly accepted definitions of the technologies, incident response processes, and community impacts. Regularizing these elements with an oversight body composed of subject matter experts in the space ensures quality work product and adoption across the corporate and governmental arenas.

2) Expanding Technical Depth. The AI Incident Database does not offer one canonical source of truth regarding AI incidents. Indeed, reasonable parties will have well-founded reasons for why an incident should be reported or classified differently. Consequently, the Database supports multiple perspectives on incidents both by ingesting multiple reports (to date, 1,199 authors from 547 publications), and by supporting multiple taxonomies for which the CSET taxonomy is an early example. The AIID taxonomies are flexible collections of classifications managed by expert individuals and organizations. The taxonomies are the means by which society collectively works to understand both individual incidents, as well as the population-level statistics for these classifications. Well structured and rigorously applied AI incident taxonomies have the ability to inform research and policy making priorities for safer AI, as well as help engineers understand the vulnerabilities and problems produced by increasingly complex intelligent systems.

The CSET taxonomy is a general taxonomy of AI incidents involving several stages of classification review and audit to ensure consistency across annotators. The intention behind the CSET taxonomy is to inform policy makers of impacts. Even with the success of the CSET taxonomy for policy makers, the AIID still lacks a rigorous technical taxonomy. Many technical classifications informing where AI is likely to produce future incidents are not currently captured. Identifying unsafe AI and motivating the development of safe AI requires technical classification.

3) Expand Database Breadth. The AI Incident Database is built on a document database and a collection of serverless browser applications. This means that the database is highly extensible to new incident types and scalable to a very large number of incident reports. In short, the database architecture anticipates the need to record an increasing number of highly varied and complex AI incidents. While a large number of incidents currently in the database have been provided by the open source community, we know we are currently missing many incidents that should be included in the current criteria. This is one area where everyone has a role in the successful development of our collective perspective into AI incidents.

How can you help?

The AI Incident Database will not succeed without your input of incidents and analysis. When encountering an AI Incident in the world, we implore you to submit a new incident record to the database. We additionally ask that software engineers and researchers work with the codebase and dataset to engineer a future for humanity that maximally benefits from intelligent systems.