🔬 Research Summary by Arun Teja Polcumpally, a Non-Resident Fellow, Center of Excellence – AI for Human Security, Doctoral fellow at Jindal School of International Affairs, India.

[Original paper by Frans af Malmborg and Jarle Trondal]

Overview: This article explores the impact of the European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Act (EU AI Act) on Nordic policymakers and their formulation of national AI policies. This study investigates how EU-level AI policy ideas influence national policy adoption by examining government policies in Norway, Sweden, Finland, Iceland, and Denmark. The findings shed light on the dynamics between ideational policy framing and organizational capacities, highlighting the significance of EU regulation in shaping AI policies in the Nordic region.

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has garnered substantial attention due to its horizontal impact on society. Scholars worldwide have extensively discussed the challenges associated with AI regulation, given its loose conceptualization and intricate interactions with socio-economic activities. In this context, the European Union’s recent release of the EU AI Act, a comprehensive draft regulation approved by the EU parliament, holds significant relevance. Being the first of its kind in the democratic world, this regulation is poised to profoundly influence AI policies globally. However, there is still a trilogue between the European Commission, parliament, and the Council before this AI act draft is enacted across Europe. For all the member states to accept the proposed draft with minimal changes, it has to be accepted, and the EU as an organization should substantially impact the member state’s policymakers. This article attempts to look at the possible influence that the EU has on the Nordic countries. It focuses specifically on the impact of the EU AI Act on Nordic policymakers and the subsequent crafting of their own AI policies.

Key Insights

While the study does not explicitly mention the theories of social construction from ‘Science Technology and Society’ and securitization from ‘International Relations,’ its explanation of how the EU influences Nordic countries aligns with the securitization concept and the theory of social construction of technology. The social construction of technology posits that societal factors shape technological inventions and societal adoptions, influencing scientists and developers. In line with the theory of social constructivism, this paper argues that EU policies on AI influence national policymakers in Nordic countries. The study further emphasizes that EU policymakers instill a sense of importance and urgency in national policymakers, resembling the securitization of AI. Although the securitization theory is typically applied to the national environment, from this article, it appears that it can be expanded to the European Union, where EU policymakers securitize AI for the member states.

The paper successfully attempts to verify two hypotheses.

H1: National policymakers will likely be influenced by EU-level AI policy ideas, leading to national policy adoption.

H2: National policymakers in the field of AI are likely to be simultaneously constrained and enabled by existing organizational capacities. Thus, policy adoption is expected to correlate positively with national organizational capacities.

To test the hypotheses, the researchers conducted a qualitative analysis of government policies in Nordic countries: Norway, Sweden, Finland, Iceland, and Denmark. The analysis involved utilizing NVivo software, which aided in segmenting keywords in policy documents, identifying themes from interview transcripts, and creating network maps of these themes. In addition to the document analysis, they also conducted interviews with the relevant policymakers which helped to substantiate their arguments.

Findings

The analysis revealed interesting insights into the influence of EU AI regulation on Nordic policymakers. Hypothesis H1 is accepted as per the data and the limited analysis from the interviews. EU is identified to successfully utilize the participation of the member states and put the AI policy narratives into the public domain. These narratives became the only ones that are on the internet, which the member states’ policymakers can access. However, interestingly, many AI

initiatives in the Nordic countries originated from external sources rather than the government, indicating a lack of expertise within governmental bodies regarding AI-related issues. This also substantiates the

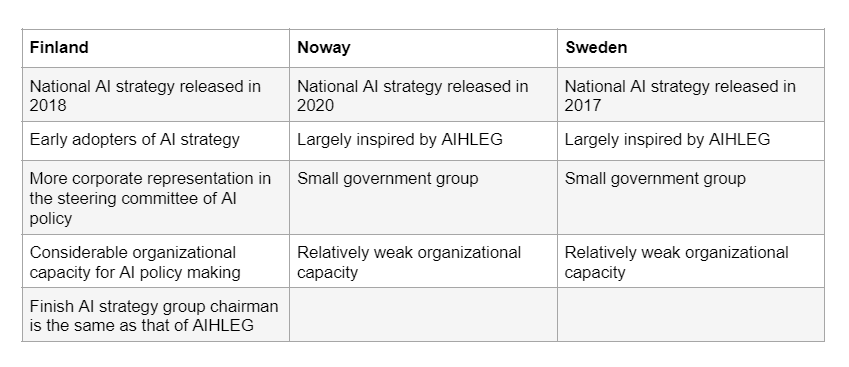

Furthermore, the study found that after the EU released a coordinated AI policy in 2017, Nordic countries’ policy documents from 2018 started referencing the EU frameworks. This suggests that policymakers in these countries adopted the approaches and frameworks developed in Brussels, aligning their national policies with EU guidelines. Below is a table presenting the major findings from the analysis of AI strategy documents of Finland, Norway, and Sweden.

In addition to exploring the impact of EU AI regulation on Nordic policymakers, the study highlights the role of European administrative integration. Despite various political debates and challenges faced by the EU, such as Brexit, COVID-19, and Eurosceptic populism, the administrative apparatus of the European Commission successfully coordinates policy through framing. This indicates the forward-looking and robust nature of European administrative integration.

Between the Lines

While this research establishes coordination between EU policymakers and member states’ policymakers, it is essential to consider the potential influence of private companies in shaping the EU’s AI approach or policy. In the research paper, it is mentioned that Finland’s AI policy is majorly shaped by private companies. Further, most of the AI initiatives came from outside the government.

This further shows a lack of human resources to perform risk assessment and design risk management frameworks for AI in Finland.

However, it is best for European countries to adopt a single AI framework for regulation. Considering individual countries in isolation may weaken the market size and technological capacity within the larger EU context.

Moreover, despite being approved by the EU parliament in June 2023, the EU AI Act has faced criticism from European industries. Some argue that the stringent measures imposed by the Act may drive AI companies away from Europe. Nonetheless, based on the study’s findings, it appears that the EU AI Act could greatly influence Nordic policymakers, potentially leading to its adoption by member states with minimal modifications.

In summary, this study sheds light on the influence of EU AI regulation on Nordic policymakers. It provides insights into the relationship between EU-level policies and national policy adoption in the field of AI. By examining government policies and considering the inputs from the bureaucracy, the study reveals the dynamics and mechanisms at play in shaping AI policies in the Nordic region.