🔬 Research Summary by Dr. Cristian Gherhes, Founder & CEO of Lexverify and Visiting Fellow at Oxford Brookes University.

[Original paper by Cristian Gherhes, Zhen Yu, Tim Vorley, and Lan Xue]

Overview: The paper examines the technological trajectories of AI in Canada and China, showing that these are the outcome of the structure-agency interplay at the national level. Tracing the development and diffusion of AI from its inception point, it provides an in-depth account of its different trajectories across the two geographical contexts, highlighting the emergence of varieties of AI at the national level.

Introduction

What direction will future progress in AI take? This is one of the most important questions of our time, especially given recent rapid advances in AI and the advent of technologies like ChatGPT. We noticed early on that countries have developed their own approaches to AI development, some launching national AI strategies while others seeking specific applications. In a broader technological context, we are yet to understand how, and more importantly why, technological trajectories differ across countries. Some have highlighted the role of institutions as structures that govern our actions, while others have pointed to agency— the capacity of actors to influence institutions.

We developed a structure-agency analytical framework, hypothesizing how actors (e.g., influential scientists, universities, political leaders, start-ups, and government) interact with institutions to shape technological development and diffusion across time. The latter include formal institutions, i.e., written rules and regulations (e.g., science, technology, innovation policies, R&D tax credits), and informal institutions, i.e., unwritten rules like attitudes, norms, values, and what we commonly understand as culture.

Using this framework and drawing on 125 in-depth interviews with a broad range of stakeholders, we demonstrate how the structure-agency interplay at the national level has resulted in nationally-specific AI trajectories in the two countries, giving rise to emerging varieties of AI.

Key Insights

Exploring AI trajectories in Canada and China

We show how key differences in the two countries’ institutional contexts and the type of actors involved at different stages have led to distinct, nationally-specific AI trajectories: one focused on technology development and ethics in Canada and one driven by the market through commercial applications in China.

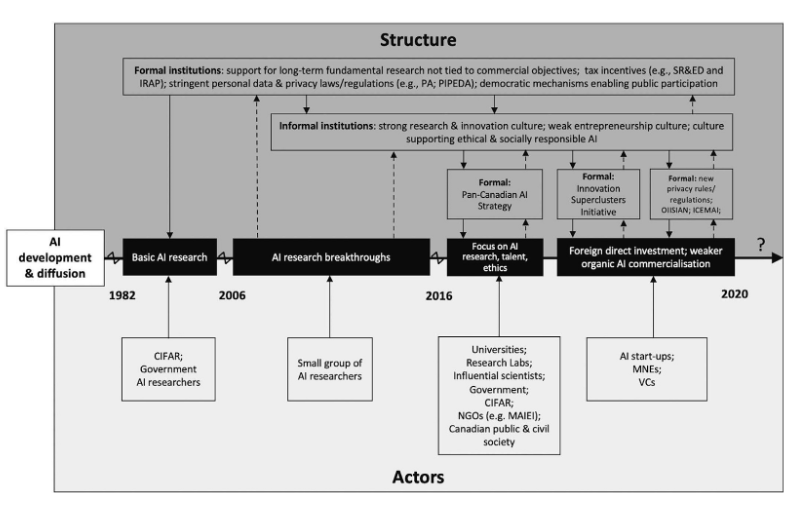

The AI trajectory of Canada: from AI winter to excellence in AI research, talent development, and ethics

Canada’s AI trajectory is shaped by a rather stable institutional structure that stimulates long-term research and scientific innovation and promotes the ethical application of AI. This has generated a strong focus on AI research and talent development, underpinned by an ethical approach rooted in culture, with slower organic commercialization of AI.

The strong role of formal institutions in fostering a culture of scientific research and innovation is particularly evident in the early phase of AI development (1982–2015) through continued AI research funding provided by the government. This enabled a small group of AI researchers—the now famous godfathers of AI—to overcome the AI winter of the 1980s—1990s and to carry on with their research. This later paid off, with scientific breakthroughs such as deep learning (2006) and generative adversarial networks (2014) reviving global interest in AI.

On the other hand, a weak entrepreneurship culture coupled with more stringent privacy laws and regulations has led to slower organic commercialization of AI technologies, prompting state-led initiatives to stimulate AI applications. This points to broader informal institutional challenges as an underdeveloped entrepreneurship culture and risk aversion appear to constrain high-growth entrepreneurial activity.

Entrepreneurial experimentation only started to take off around 2016, when we see a proliferation of AI start-ups, multinational enterprises (MNEs), and foreign tech giants setting up shop in Canada’s AI hubs. With this, we start to see the emergence of an ecosystem promoting AI development and diffusion at scale. New support initiatives for entrepreneurs and businesses incentivized AI start-up activity and AI applications. At the same time, the launch of the Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy solidified support for AI research and innovation.

A characteristic of Canada’s AI trajectory is a strong focus on ethics that reflects deeply embedded cultural values. Efforts to align AI with Canadian values have seen a more seamless translation of ethical and socially responsible AI development preferences into formal institutions through various policy instruments and public initiatives. From academia to industry experts and the general public, we see wide participation in publicly-funded and third-sector-led initiatives, including the Montreal AI Ethics Institute (MAIEI), that promote ethical AI.

However, Canada’s AI strengths remain rooted in research and talent development, with AI commercialization lagging.

Figure 1: AI development and diffusion in Canada

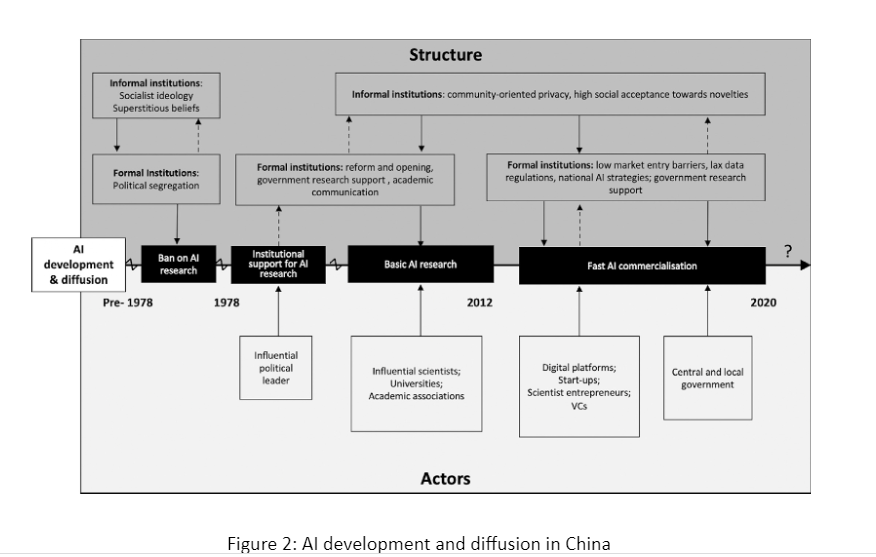

The AI trajectory of China: from fast commercialization to ethical considerations and global AI leadership ambitions

In China, a dynamic and loose institutional structure characterized by lax regulations, low entry barriers, and high openness to novelties has resulted in a market-driven AI trajectory focused on technology commercialization. This sees domestic tech giants and the government as dominant players in mobilizing innovation resources and commercializing AI.

Though not a pioneer in AI research, China started to capitalize on AI’s commercial potential early on. Formal and informal institutional support for basic AI research since the 1980s was gained by changes in political discourses and the influence of leading scientists and academic organizations. However, the driving structural force behind AI commercialization is a mix of laxer regulations, lower entry threshold, vast domestic market, and consumer openness towards novelties, which have spurred early and fast AI commercialization at scale.

Post-2012, domestically-born digital giants and the government have become key actors that are critical and active in driving AI development and diffusion, propelling AI to the top of the national agenda and prompting significant state support. Importantly, the ascent of tech giants and their accumulation of power enables them to mobilize important innovation resources to speed up AI commercialization and act as agents of change in shaping the institutional environment.

Like Canada, informal institutions also play a key role in the diffusion of AI within the country. Specifically, Chinese traditional perceptions of privacy are more related to collectivism, ‘saving face,’ and community-oriented values, which lead to different societal preferences compared to the West. These are believed to have enabled AI’s faster commercialization and adoption at scale.

At the same time, more recently, we saw China trying to balance data exploitation and protection. The introduction of national laws on data security and personal information protection, voluntary standards such as the Personal Information Security Specification published and trialed by companies like Tencent and Alipay, the Beijing AI Principles, and ambitions to participate in international AI governance all point to an increased concern with AI ethics and governance and a potential shift in the current trajectory.

What are the implications for future progress in AI?

The trajectories of emerging technologies like AI are not definitive but in constant flux, where actors can influence their evolution through various mechanisms. This relates to a key issue in technology studies that concerns human agency: the extent to which actors can shape technology development. Here, our findings challenge the acceptance of technological determinism and the imminence of potentially negative consequences of AI applications.

We show, for example, how actors can resist and oppose unwanted technological outcomes in Canada and how they can create new structures in China. This means it is within our power to influence the trajectories of emerging technologies. In fact, we can conclude that the future progress of emerging technologies like AI will be influenced by the choices made by societies and nations, by all of us, around the world.

Predicting the future direction of AI is like looking into a crystal ball. One thing seems certain, though. In the short to medium term, and in the absence of a globally concerted approach to regulating and governing AI (which in the current global context seems challenging at best), nations will be left to decide on their own or as a group what AI endeavors they should pursue as they aim to defend national values and interests. We are, therefore, likely to see different ‘faces’ of AI worldwide. We can and should choose carefully.