🔬 Research Summary by 1) Natalia Díaz Rodríguez, 2) Javier Del Ser, 3) Mark Coeckelbergh, 4) Marcos López de Prado, 5) Enrique Herrera-Viedma, and 6) Francisco Herrera

1) Assistant Professor, University of Granada, Spain, DaSCI Andalusian Research Institute in Data Science and Computational Intelligence, website: https://sites.google.com/view/nataliadiaz;

2) Research Professor in Artificial Intelligence, TECNALIA, Basque Research & Technology Alliance (BRTA), Spain; and Department of Communications Engineering, University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU), 48013 Bilbao, Spain;

3) Department of Philosophy, University of Vienna, Vienna, 1010, Austria;

4) School of Engineering, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, 14850, United States; ADIA Lab, Al Maryah Island, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; and Department of Mathematics, Khalifa University of Science and Technology, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates;

5) Full Professor, DaSCI Andalusian Research Institute in Data Science and Computational Intelligence, University of Granada, Spain;

6) Full Professor, DaSCI Andalusian Research Institute in Data Science and Computational Intelligence, University of Granada, Spain;

[Original paper by Díaz-Rodríguez, N., Del Ser, J., Coeckelbergh, M., López de Prado, M., Herrera-Viedma, E., & Herrera, F.]

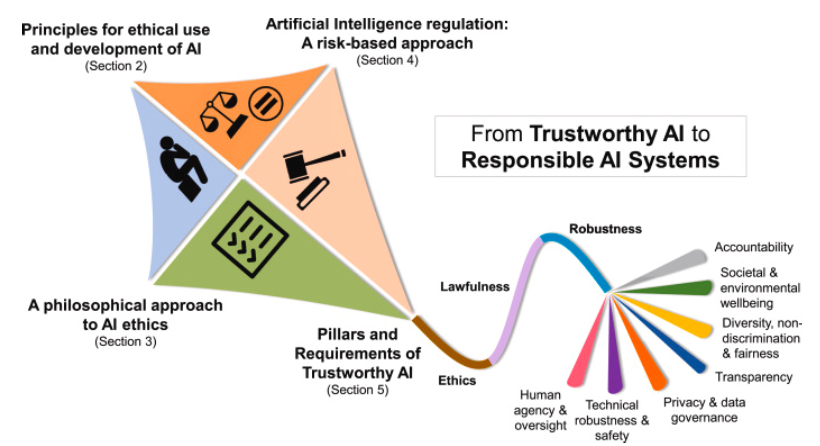

Overview: This paper presents a holistic vision of trustworthy AI through the principles for its ethical use and development, a philosophical reflection on AI Ethics, an analysis of regulatory efforts around trustworthy AI, and an examination of the fundamental pillars and requirements for trustworthy AI. It concludes with a definition of responsible AI systems, the role of regulatory sandboxes, and a debate on the recent diverging views about AI’s future.

Introduction

Recently, a family of generative AI (DALL-E 2, Imagen, or large language model (LLM) products such as ChatGPT) have sparked many debates. These arise as a concern on what this could mean in all fields of application and what impact they could have. Debates emerge from the ethical principles’ perspective, from the regulation ones, from what it means to have fair AI, or from the technological point of view, on what an ethical development and use of AI systems really mean. The notion of trustworthy AI has attracted particular interest across the political institutions of the European Union (EU), which have intensively worked on elaborating this concept through a set of guidelines based on ethical principles and requirements for trustworthy AI.

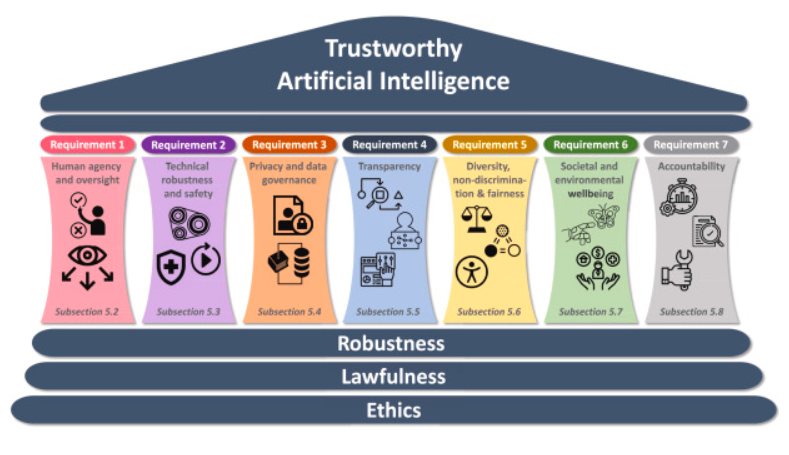

Trustworthy AI is a holistic and systemic approach that is a prerequisite for people and societies to develop, deploy and use AI systems. It is composed of three pillars and seven requirements: the legal, ethical, and technical robustness pillars; and the following requirements: human agency and oversight; technical robustness and safety; privacy and data governance; transparency; diversity, non-discrimination and fairness; societal and environmental wellbeing; and accountability. Although the previous definition is based on requirements, a larger multidimensional vision exists. It considers the ethical debate per se, the ethical principles, and a risk-based approach to regulation backed up by the EU AI Act.

This work offers a primer for researchers and practitioners interested in a holistic vision of trustworthy AI from 4 axes (Fig. above; from ethical principles and AI ethics to legislation and technical requirements).

This vision is described in the paper by:

1. Providing a holistic vision of the multifaceted notion of trustworthy AI and its diverse principles seen by international agencies, governments, and the industry.

2. Breaking down this multidimensional vision of trustworthy AI into 4 axes to reveal the intricacies associated with its pillars, its technical and legal requirements, and what responsibility in this context really means.

3. Examine what each requirement for trustworthy AI means, why it is necessary and proposed, and how it is being addressed technologically.

4. Analyzing AI regulation from a pragmatic perspective to understand the essentials of the most advanced legal piece, the European Commission perspective.

5. Defining responsible AI systems as the result of connecting the many-sided aspects of trustworthy AI and whose design should be guided by regulatory sandboxes.

6. Dissecting currently hot debates on the status of AI, the moratorium letter to pause giant AI experiments, and current movements around an international regulation.

Key Insights

Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence: Pillars and Requirements

In a technical sense, trustworthiness is the confidence of whether a system/model will act as intended when facing a given problem. For instance, trust can be fostered when a system provides detailed explanations of its decisions. Likewise, trust can be bolstered if the user is offered guarantees that the model can operate robustly under different circumstances, respects privacy, or does not get affected by biases present in the data from which it learns.

Trustworthiness is, therefore, a multifaceted requisite for people and societies to develop, deploy and use AI systems and a sine qua non condition for realizing the potentially vast social and economic benefits AI can bring. Moreover, trustworthiness does not concern only the system itself but also other actors and processes that take their part during the AI life cycle. This requires a holistic and systemic analysis of the pillars and requirements that contribute to the generation of trust in the user of an AI-based system.

The thorough analysis of the seven requirements proposed by the European Commission’s High-Level Expert Group (HLEG) is summarized in the figure below:

Responsible Artificial Intelligence systems

A little prior to trustworthy AI is responsible AI, which has been widely used as a synonym. In the paper, we make an explicit statement on the similarities and differences that can be established between trustworthy and responsible AI. The main aspects that make such concepts differ are that responsible AI emphasizes the ethical use of an AI-based system and its auditability, accountability, and liability.

In general, when referring to responsibility over a certain task, the person in charge assumes the consequences of his/her actions/decisions to undertake the task, whether they are eventually right or wrong. When translating this concept of responsibility to AI-based systems, decisions issued by the system in question must be accountable, legally compliant, and ethical. Other requirements for trustworthy AI (e.g., robustness or sustainability) may not be relevant to responsibility. Therefore, trustworthy AI provides a broader umbrella that contains responsible AI and extends it toward considering other requirements that contribute to the generation of trust in the system. It is also worth mentioning that providing responsibility over AI products links to the provision of mechanisms for algorithmic auditing (auditability), which is part of requirement 7 (Accountability). To stress the importance of responsible development of AI and to bridge the gap between trustworthy AI in theory and practice and regulation, the authors provide the following definition:

A Responsible AI system requires ensuring auditability and accountability during its design, development, and use, according to specifications and the applicable regulation of the domain of practice in which the AI system is to be used.

The rest of the paper discusses the philosophical approach to AI ethics, the risk-based approach to regulating the use of AI systems, and how AI systems can comply with regulation in high-risk scenarios.

The importance of AI regulatory sandboxes as a challenge for auditing algorithms

Once requirements for HRAIs have been established, one of the remaining challenges is making the AI system comply appropriately. Such requisites (AI Act, Chapter 2, Art. 8–15) motivate the need for a test environment to audit AI-based systems through the latter’s safe and harmonized procedures. Regulatory sandboxes are indeed recommended by the AI Act (Chapter 5, Art. 53–54) since algorithms should comply with regulations and can be tested in a safe environment before entering the market. This auditing process can be implemented via regulatory sandboxes.

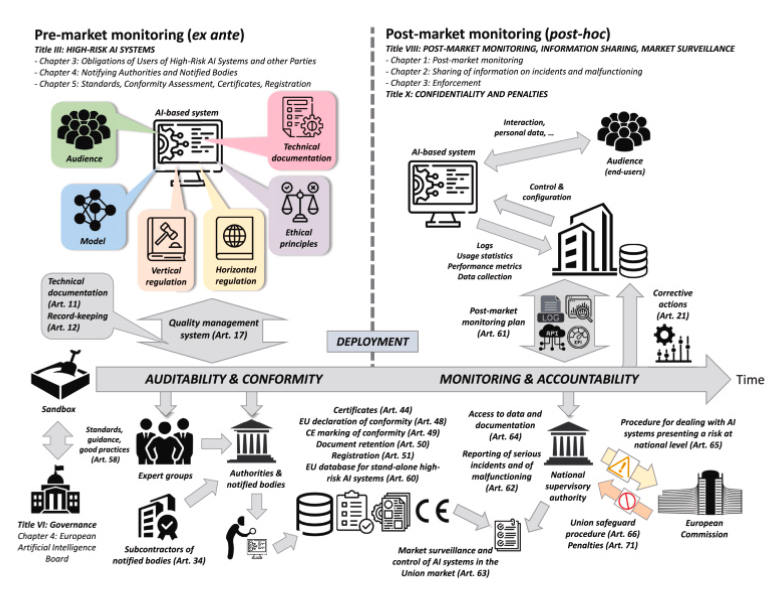

The role of sandboxes before (ex-ante) and after (post-hoc) the AI-based system has been deployed in the market is a key to its auditability and accountability. Sandboxes permit evaluating the AI-based system’s conformity with respect to technical specifications, horizontal & vertical regulation, and ethical principles in a controlled and reliable testing environment. Once conformity has been verified, sandboxes can interface with the deployed AI-based asset via established monitoring plans, so that information about its post-market functioning can be collected and processed. This information is used by the national supervisory authority to evaluate its compliance:

In this context, we distinguish between:

1. Auditability: As an element to aid accountability, a thorough auditing process aims to validate the conformity of the AI-based asset under target to (1) vertical or sectorial regulatory constraints; (2) horizontal or AI-wide regulations (e.g., EU AI Act); and (3) specifications and constraints imposed by the application for which it is designed.

2. Accountability: It establishes the liability of decisions derived from the AI system’s output once its compliance with the regulations, guidelines, and specifications imposed by the application for which it is designed has been audited.

Within the context of the European approach and AI Act, this translates into a required pre-market use of regulatory sandboxes and the adaptability of the requirements and regulation for trustworthy AI into a framework for the domain of practice of the AI system.

Between the lines

The idea of this paper is to serve as a guiding reference for researchers, practitioners, and neophytes interested in trustworthy AI from a holistic perspective. It analyzes what trust in AI-based systems implies in practice and its requirements for the design and development of responsible AI systems throughout their life cycle. We also highlight the urgent need for dynamic regulation and evaluation protocols in view of the rapid technological evolution and increasing capabilities of emerging AI systems.

Our overarching conclusion is that we should not regulate scientific progress in AI but rather products and their usage. We claim that regulation is the key to consensus. Thereby, trustworthy and responsible AI systems are crucial in high-risk scenarios to catalyze technological progress and regulation convergence, always in compliance with ethical principles.