[Original paper by David Gray Widder and Dawn Nafus]

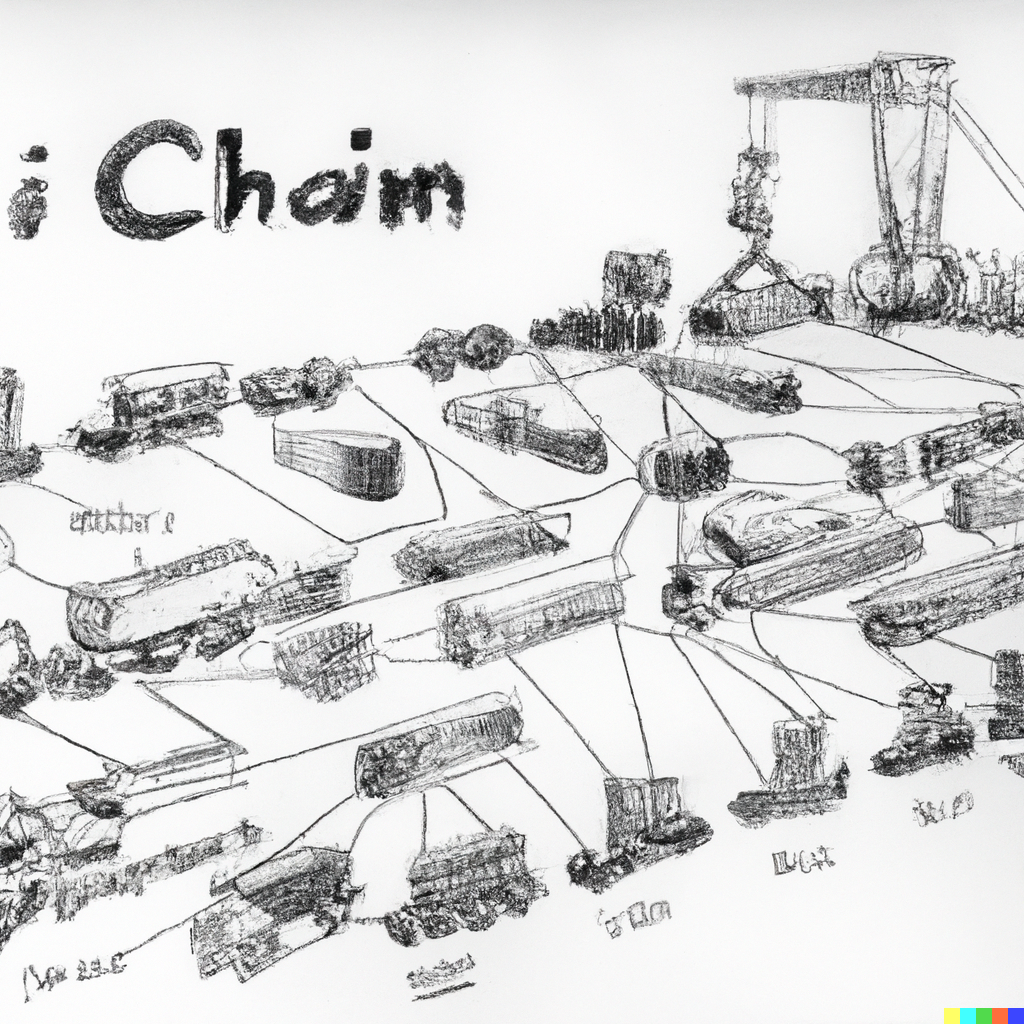

Overview: AI system components are often produced in different organizational contexts. For example, we might not know how upstream datasets were collected or how downstream users may use our system. In our recent article, Dawn Nafus and I show how software supply chains make AI ethics work hard and how they lead people to disavow accountability for ethical questions that require scrutiny of upstream components or downstream use.

Introduction

OpenAI has been in the news lately: it has disavowed accountability for the low pay and poor working conditions of the data labelers who filter traumatic content from ChatGPT because they had outsourced this work to a subcontractor. This echoes past debates on ethics in supply chains: Nike at first disavowed the sweatshop working conditions in which its shoes were produced because they had outsourced this to a subcontractor.

Our research shows how dislocated organizational contexts in AI supply chains make it easy to disavow accountability for ethical scrutiny – both upstream components (e.g., is this dataset biased?) or downstream uses (e.g., how could people use my system for harm?). This was based on interviews with 27 global AI practitioners, from data labelers, academic researchers, and framework builders to model builders to those building end-user systems, in which we asked them what ethical issues they saw as within their ability and responsibility to address.

Key Insights

Doing AI ethics well requires you to know a lot. For example, if using existing datasets or pretrained models, you want to know whether they exhibit bias, which can be challenging to answer if you didn’t collect the data or train the model. Also, you might want to know how people will use your system so you can think about what bias would even mean in that context or think about how people may misuse it.

However, like many software systems, AI is often built on the idea of “modularity”: we reuse standard components and create our systems to be modular so that no single person needs to understand how each and every piece works (implementation), only how to use it (interface). This manages complexity and helps us build large systems without one person or organization needing to know the innards of, or control, each module in the supply chain.

However, we show in the paper that the ethos of Modularity has important ethical drawbacks: it makes it harder to know the answers to upstream (dataset bias?) and downstream (context? misuse?) questions that are important when thinking about ethics, and therefore it makes it harder to feel responsible for doing this kind of work. In short: the AI system’s supply chain nature leads people to disavow responsibility for thinking about ethics because it fractures the knowledge that would be needed to do so. We show various ways that AI supply chains inflect this disavowal, enabling division of labor, the rush to scale, and status hierarchies between ethics tasks and the “real work” of building systems.

How can we proceed? We draw on Lucy Suchman’s notion of located accountability, which suggests that to build responsible systems, we must understand their creation as an “entry into the networks of working relations.” This means looking for links that may remain in the AI supply chain, and our participants show possibilities for action in the logic of “customer centricity,” marketing, kinships and friendships, and opportunities for soft resistance.

We conclude by suggesting possible ways forward: (1) we could work within modularity by better delineating who is responsible for which ethical tasks in AI supply chains to better distribute ethical accountability; (2) we could seek to strengthen interfaces in the AI supply chain so it is easier to ethics work that requires many partial perspectives to meet; and finally (3) we may imagine radically different modes of solving problems that do not depend on modular supply chains.

Between the lines

Right now, we’re seeing enormous debate about how to regulate AI systems. However, I am worried that too often, this debate talks about “AI” as if it is created by one monolithic actor, often a company releasing an end-user system. We can build more robust regulation if we find more places to locate accountability, scrutinizing not only final systems but also the components used to create them. Richmond Wong and I explored policy levers higher upstream in AI supply chains in a two-page follow-up piece. Blair Attard-Frost and I showed how the related concept of Value Chains can help integrate and situate AI ethics work in a recent preprint. Others have also explored accountability in AI supply chains, and these ideas have begun to filter into resources for EU policymakers and regulators. Let’s hope this continues!