🔬 Research Summary by Charlotte Siegmann and Markus Anderljung

Charlotte Siegmann is a Predoctoral Research Fellow in Economics at the Global Priorities Institute at Oxford University.

Markus Anderljung is the Head of Policy and a Research Fellow at the Centre for the Governance of AI.

[Original paper by Charlotte Siegmann and Markus Anderljung]

Overview: EU policymakers want the EU to become a regulatory superpower in AI. Will they succeed? While parts of the AI regulation will most likely not diffuse, other parts are poised to have a global impact.

Introduction

The European Union (EU) introduced among the first, most stringent, and most comprehensive AI regulatory regimes of major jurisdictions. Our report asks whether the EU’s regulation for AI will diffuse globally, producing a so-called “Brussels Effect.” In 2019, two of the most powerful European politicians, Ursula von der Leyen and Angela Merkel, called for the European Union to create a GDPR for AI – hinting at this ambition. [1]

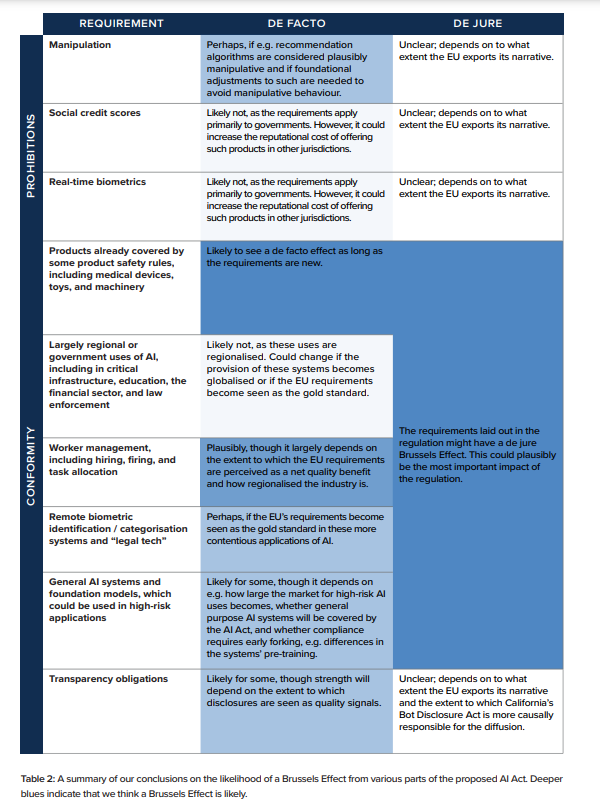

We consider both the possibility that the EU’s AI regulation will incentivize changes in products offered in non-EU countries (a de facto Brussels Effect) and the possibility it will influence regulation adopted by other jurisdictions (a de jure Brussels Effect). Focusing on the proposed EU AI Act, we tentatively conclude that de facto and de jure Brussels Effects are likely for parts of the EU regulatory regime. A de facto effect is particularly likely to arise in large US tech companies with ”high-risk” AI systems as defined by the EU AI Act. This regulation might be significant as an operationalization of trustworthy and human-centered AI development and deployment.

If the EU regime is likely to see significant diffusion, ensuring it is well-designed becomes a matter of global importance.

Key Insights

For parts of the EU’s AI regulation, a de facto Brussels Effect is likely

We expect multinational companies to offer some EU-compliant AI products outside the EU. Once a company has decided to produce an EU-compliant product for the EU market, it will sometimes be more profitable to offer that product globally rather than offering a different non-compliant version outside the EU.

Several factors make this behavior (“non-differentiation”) more likely.

- The EU has relatively favorable market properties. In particular, the market for AI-based products is large and heavily serviced by multinational firms. The EU market size incentivizes firms to develop and offer EU-compliant products rather than simply abandoning the EU market. The presence of multinational firms opens the door to a de facto effect.

- The EU’s AI regulation is likely to be especially stringent. If it were not more stringent than other jurisdictions’ regulations on at least some dimensions, then a Brussels Effect is not possible.

- The EU has a high regulatory capacity. The EU’s ability to produce well-crafted regulations makes them less difficult to enforce and cumbersome to comply with. EU compliance might also be seen as a sign of the trustworthiness of the product, further incentivizing firms to offer EU-complaint products in other jurisdictions.

- Demand for some affected AI products is likely to be fairly inelastic. Compliance with EU AI rules may raise the cost or decrease the quality of AI products by reducing product functionality. If demand were too elastic in response to such changes in cost and quality, then this could shrink the size of the EU market and make multinational firms more willing to abandon it. It would also make offering EU-compliant products outside the EU more costly.

- The cost of differentiation for some, but not all, AI products is likely to be high. Creating compliant and non-compliant versions of a product may require developers to practice “early forking” (i.e., changing a fundamental feature early on in the development process) and maintain two separate technology stacks in parallel. Suppose a company has decided to develop a compliant version of the product. In that case, offering this same version outside the EU may allow them to cut development costs without comparably large costs of non-differentiation, e.g., the costs of offering EU-compliant products globally.

The AI Act introduces new standards and conformity assessment requirements for “high-risk” AI products sold in the EU, estimated at 5–15% of the EU AI market. We anticipate a de facto effect for some high-risk AI products and for some categories of requirements, but not others, owing to variation in how strongly the above factors apply. A de facto effect is particularly likely, for instance, for medical devices, some worker management systems, certain legal technology, and a subset of biometric categorization systems. A de facto effect may be particularly likely for requirements concerning risk management, record-keeping, transparency, accuracy, robustness, and cybersecurity. A de facto effect is less likely for products whose markets tend to be more regionalized, such as creditworthiness assessment systems and various government applications.

Although so-called “foundation models” are not considered high-risk in the EU AI Act, they may also experience a de facto effect. Foundation models are general-purpose, pre-trained AI systems that can be used to create a wide range of AI products. Developers of these models may wish to ensure that AI products derived from their models will satisfy certain EU requirements by default. In addition, the EU AI Act proposal may also be amended to introduce specific requirements on general-purpose systems and foundation models (as has been the case recently).

The EU AI Act also introduces prohibitions on certain uses of AI systems. There is a small chance that prohibitions on the use of “subliminal techniques” could have implications for the design of recommender systems.

A de jure Brussels Effect is also likely for parts of the EU’s AI regulation

We expect that other jurisdictions will adopt some EU-inspired AI regulation. This could happen via several channels:

- Foreign jurisdictions expect EU-like regulation to be high quality and consistent with their own regulatory goals.

- The EU promotes its blueprint.

- A de facto Brussels Effect incentivizes a jurisdiction to adopt EU-like regulations, as it, for instance, reduces the additional burden that is placed on companies serving both markets via adoption.

- The EU actively incentivizes the adoption of EU-like regulations, for instance, through trade rules.

De jure diffusion is particularly likely for jurisdictions with significant trade relations with the EU, as introducing requirements incompatible with the AI Act’s requirements for “high-risk” systems would impose frictions to trade. There is also a significant chance that these requirements will produce a de jure effect by becoming the international gold standard for the responsible development and deployment of AI.

A de jure effect is more likely for China than for the US, as China has chosen to adopt many EU-inspired laws in the past. However, China is unlikely to include individual protections from state uses of AI. Further, China has already adopted some new AI regulations, somewhat reducing the opportunity for a de jure effect.

We summarize our conclusions on the likelihood of a Brussels Effect from various parts of the proposed AI Act. Deeper blues indicate that we think a Brussels Effect is likely.

Between the lines

If there is a significant AI Brussels Effect, this could lead to stricter AI regulation globally. The details of EU AI regulation could also influence how “trustworthy AI” is conceived worldwide, shaping research agendas to ensure the safety and fairness of AI systems. Ultimately, the likelihood of a Brussels Effect increases the importance of helping shape the EU AI regulatory regime: getting the regulation right would become a matter of global importance.

A stronger Brussels Effect may suggest other jurisdictions can significantly influence AI regulation beyond their borders. A strong AI Brussels Effect could increase the chance that, e.g., US states introducing AI regulation (perhaps that is EU-compatible) would produce regulatory diffusion within the US.

The report prompts further questions:

- Will other parts of the EU regulatory regime for AI see diffusion, e.g., the Digital Services Act and the Digital Markets Act?

- If we expect a de facto Brussels Effect to be likely, how does that update us on the importance of corporate self-governance efforts in AI? It could suggest that self-governance efforts, too could see global diffusion and become more critical.

References

[1] Directorate-General for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations, “Speech by President-Elect von Der Leyen in the European Parliament Plenary on the Occasion of the Presentation of Her College of Commissioners and Their Programme,” European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations, November 27, 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/news/speech-president-elect-von-der-leyen-european-parliament-plenary-occasion-presentation-her-college-2019-11-27_en; EPIC, “At G-20, Merkel Calls for Comprehensive AI Regulation,” EPIC – Electronic Privacy Information Center, June 28, 2019, https://epic.org/at-g-20-merkel-calls-for-comprehensive-ai-regulation/