This is an edited transcript of The State of AI Ethics Panel we hosted on March 24th, where we discussed The Abuse and Misogynoir Playbook (the opening piece of our latest State of AI Ethics Report) and the broader historical significance of the mistreatment of Dr. Timnit Gebru by Google.

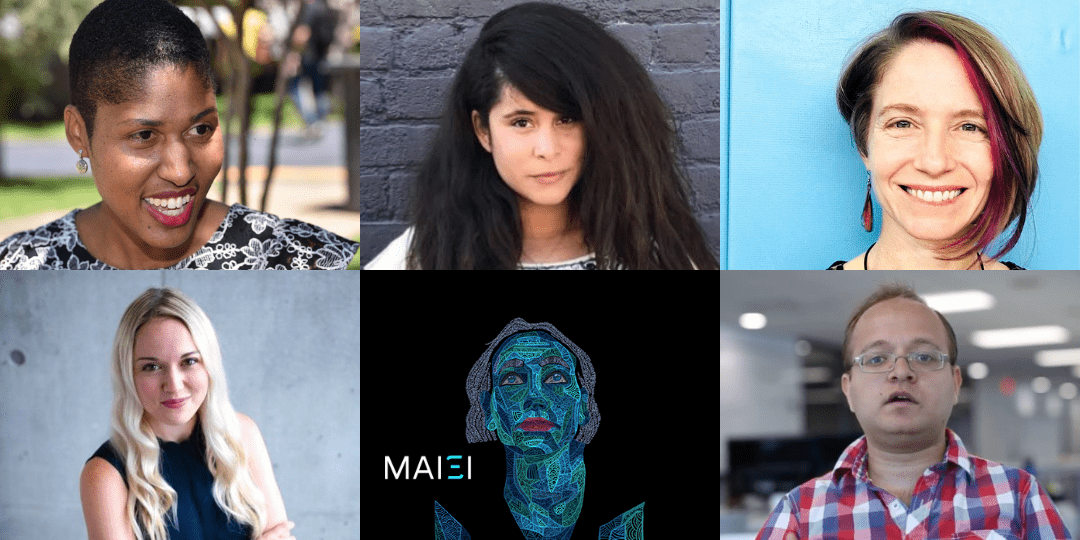

On the panel were:

- Danielle Wood — Assistant Professor in the Program in Media Arts & Sciences, MIT (@space_enabled)

- Katlyn M Turner — Research Scientist, MIT Media Lab (@katlynmturner)

- Catherine D’Ignazio — Assistant Professor of Urban Science and Planning in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning, MIT (@kanarinka)

- Victoria Heath (Moderator) — Associate Director of Governance & Strategy Montreal AI Ethics Institute (@victoria_heath7)

- Abhishek Gupta – Founder, Montreal AI Ethics Institute (@atg_abhishek)

Introduction to The Abuse and Misogynoir Playbook

Victoria: Before we dig deeper into The Abuse and Misogynoir Playbook, I want to make sure our audience has a basic understanding of the term “misogynoir.” Please define this term and explain briefly its context in the field of AI.

Katlyn: Misogynoir is the racist gendered lens that Black women have faced historically and continue to face today. There’s this taboo for Black women of using labor, using intelligence, and using those skills to advance one’s own interests or one’s community interests. That is the phenomenon we’re drawing from in this piece, and we tried to show that this is not something that only tech does, but really every sector of society has this way of treating Black women who are speaking truth to power, and it’s informed by misogynoir. The term itself was introduced by Dr. Moya Bailey in 2010.

Victoria: As you mention in the piece, many science and technology scholars, specifically Black women, have argued for decades that technology is not “ahistorical,” “evolved,” “rational,” or “neutral.” Rather, the instinct to assign these adjectives to technology is “part of a centuries-old playbook employed swiftly and authoritatively over the years to silence, erase, and revise contributions and contributors that question the status quo of innovation, policy, and social theory.” Can you take us through this playbook as you describe it in the report, step by step?

Katlyn: Black women are expected to do whatever people want us to do. We’re not supposed to use skills, labor, and competency to advance our own interests or the interests of our communities. So the first step of making a contribution is that it’s oftentimes using what Audre Lorde has called “the master’s tools” or the tools of society. These tools are used to advance knowledge, maybe make a leap forward, and in doing so it reveals a systemic inequity or truth that the status quo would prefer not to be revealed. And that is unacceptable in some way to the dominant class and to the various stakeholders of different systems of power.

Danielle: The first step is often disbelief, which can be either a true disbelief or perhaps a false disbelief, depending on people’s response to the contribution. One version could be people truly being surprised that a black woman has the ability to do these things. The question could be: is this being said because it is something that they truly don’t believe, or do they actually just want people to put into doubt the person’s qualities?

After this initial doubt is cast comes step 3, when people seek to justify their doubt and to convince others to share that doubt. This is also where gaslighting comes in, where phrases like “you must be mistaken” and “Is this really what happened?” are used.

Catherine: The next step is erasure — specifically of the contribution that the Black woman has made. For example, the company moves on and tries to erase the fact that this person existed or what their contributions were or what was the controversy. That person isn’t mentioned anymore. They’re not incorporated into historical tellings of how something evolved nor seen as being important to a particular field of knowledge or a particular area of inquiry. This effectively ends up de-platforming them.

Their erasure then leads to a systemic revisionism that we talk about in step five, where instead of these contributions building new knowledge forward, it is replaced with a new narrative. And if there are negative reactions to any reminders of those contributions, they’re continued to be treated with tactics like dismissal, gaslighting, and discrediting.

And then what of course happens is a loss of knowledge over generations. That’s why we have the silences in the archives, where contributions from marginalized people have been systematically erased over time.

The implications of the playbook in AI ethics

Victoria: I think it’s relatively safe to assume that many in the AI community, and in this audience, have been following the fallout from the firing of Dr Timnit Gebru from Google. What issues in AI, specifically the field of AI Ethics, has this exposed?

Abhishek: What stood out to me was the gap between what an organization claims to care about and its actions. Another thing that became clear was the tension between business objectives including profit motives versus what’s good for society. Unfortunately, the frame is adversarial right now — what’s good for the bottom line often isn’t good for the people or the planet.

Another thing that was exposed also was how effective the organizational measures are. There are bound to be conflicts that arise, but what are the organizational measures that are in place that actually help them constructively move forward? How much agency are you willing to offer these people that you bring on the team to address problems?

As we saw with Dr. Gebru, the answer, in practice, was “not much”. I think for the entire field, it just shows that there is a long way to go.

Why the past is the key to understanding today’s dark patterns

Victoria: You write in the piece that the impacts of this Playbook are devastating for Black women, causing the “erasure of valuable contributions of Black women, supplanted by a more whitewashed narrative of events, that over time the public accepts as truth.” Danielle, your experience is largely in the space industry and aeronautics and your and your co-authors write about the historical experiences of Phillis Wheatley, Ida Well, Harriett Jacobs and Zora Neale Hurston in the article. Why did you select these historical examples and how does their experience inform your work?

Danielle: Phillis had spent years studying literature and, bringing together many influences in her writing. She wrote really meaningful poetry. And she was actually poised to become the first woman in the European-colonized United States in the region under the colonial system to have a book published.

But first, there was this idea that people wouldn’t believe that she could write such poetry because they didn’t think she’d have the capability as a Black woman, as a woman from Africa, to do this. So a statue of Phillis Wheatley is located very close to my home and on beautiful days here in the Boston area, I sometimes go and see it.

Harriet Jacobs illegally wrote a book, meaning she knew how to read and write, which was illegal for people who were enslaved. She taught others to read and write illegally at her own peril, but she presented information in what was considered a well-established mode of communication. And she addresses readers thinking that these must be the readers who can help to end slavery through their votes, through their abolitionist efforts. Her message to them is “Hey, you need to understand through this writing that I’m doing, how things really are in the South.” But she’s gaslighted, and she actually describes gaslighting, giving examples, such as those who want to discourage people from running away from slavery, saying “Oh, you don’t want to escape”.

I also want to highlight Ida B Wells, who was based in Memphis, Tennessee. And again, a particular tool that she was using was in the category of journalism. And I will add data science because she was an activist focusing on the issues of lynching; she was born in 1862.

She was very diligent as an editor focusing on hosting a newspaper and was able to develop a self-sustaining business around it within the Black community. Later she saw that a close friend of hers had experienced lynching and that the police were not protecting her community, but were actually part of the mob that caused the death. Then she used data science to communicate the impacts of lynching and investigated to demonstrate that the excuses used for lynching, and for mob attacks on Black men, were not based on true evidence. And she experienced great personal danger in doing this work.

These patterns are very similar to the ones that we’re seeing today.

The present: a moment of reckoning

Victoria: There is a focus at the top of your piece on how marginalized peoples have had to fight for equity, equality, and justice for centuries in the United States, specifically. This passage especially struck me: “We can take heart that the path our field is on now is part of a long tradition questioning, perfecting, and ensuring that reality reflects our timelessly stated ideals: justice for all. And as part of that process, we can name and root out dynamics that have long been employed to preclude, erase, and silence progress.”

Katlyn, as someone who has been a part of the STEM world for many years and actively works to improve justice, equity and diversity in higher education and the industry, does this moment feel different? Are we in the midst of a reckoning?

Katlyn: I think the answer is yes to both questions. I want to go back to what Danielle was explaining earlier with some of her examples and just emphasize the point that for these individuals, for Phillis, for Harriet, for Ida, their lives were put in danger because of their contributions.

Something we’re trying to draw attention to with this article is this violent backlash that happens when we have people who are from classes that are thought of as not supposed to be making contributions, making contributions. Timnit has been very open about this on her Twitter and on her other communications about the backlash and the violence that she and her team and her collaborators have experienced as the result of trying to publish a paper that was well-researched and that had gone through peer review, only to be told that they have to retract it. And for those of you not in academia, retraction is actually a word that means something very specific. It doesn’t just mean you’re pulling the paper.

It means there’s something wrong with your science. There’s something wrong with the process that you used to come to a conclusion. It’s a very serious thing to retract a paper. So that is a very specific thing we should talk about.

There was an article, maybe in the Atlantic or the New Yorker, that had some polls saying that something like 70% of Americans today would say, “I don’t want to be a white supremacist”. They want to be anti-racist. That’s a really important thing for us to understand for all of us in this room to understand. A long time ago, it wasn’t acceptable to be abolitionist in any way, right? This was a fringe ideology. Whether you were white, African, or Indigenous, it could get you killed.

So the fact that we have so many people today that genuinely want to disavow this suggests that we’re at a point of reckoning.

Do we have a long way of work to go? Yes. And this work can’t be solved with diversity fellowships or cultural lunches at your company. We have to interrogate the epistemology of who was included and excluded when we were developing these fields. What were these fields originally intended for? If we don’t really take a targeted look at the history of different fields, and the history of different social dynamics like misogynoir and how that impacts our fields today, we’re going to keep making the same mistakes and we’ll be running into a wall over and over again.

Looking forward: surveillance from below, citizen juries, and allyship

Victoria: Catherine, I’m really interested in how your work using data and computational methods to realize gender and racial equity applies here. How do we encourage everyone to play a part in ensuring justice for all instead of placing the burden on the shoulders of the very people who are marginalized and harmed?

Catherine: Often when we talk about gender, it’s assumed we’re talking about women and like women have gender. And when we talk about race, it’s assumed we’re talking about people of color. Lauren Klein and I write in our book that it takes more than one gender to have gender inequality. And it’s going to take all of us to make a difference. Similarly, it’s going to take people from all races to work towards equality. I would like to specifically call white people in – to invite white people to make racial justice a central focus of their work.

Additionally, in technical communities, we mostly train computer scientists to care about what’s inside the machine. And this teaches them to think about computers in a way that’s abstracted and not connected to the social world. Another starting point for change is to challenge that assumption. Technology cannot be separated from the social world.

We need to think with an intersectional feminist perspective and consider how to put lived experience at the center, and treat it as a valid form of empirical data. When we were writing this piece we asked ourselves “How do we learn from these historical struggles and also help to recognize patterns?” History helps us see structural macro patterns in the world. It helps us scale up our vision and see how things today like Dr. Gebru’s situation are connected to these patterns that we still haven’t been able to break out of.

I write in our book that we do have hope for data science, computer science and technology. The most exciting potential here is the idea of surveillance from below. It’s a concept that we talk about in our book as counterdata collection. And the idea is to understand how dominant structures of power work rather than going out and extracting knowledge from marginalized communities.

You actually try to understand how power works and you try to hold power accountable. And I would like to see us apply those tools — there could be a lot of potential there.

Victoria: Abhishek, anything to add there?

Abhishek: One of the ways to operationalize the system is through citizen juries. Meaning, bringing in those stakeholders who are a core part of your design development and deployment process. And that’s something that we’re starting to see a few organizations put into practice, including Microsoft.

None of these processes are perfect, especially because the concerns and needs of different communities evolve over time, which is something that we need to be sensitive to. From a project management standpoint, all of us love to check off boxes and declare that a project is done. But this doesn’t work that way. This needs to be an evolving and ongoing conversation where we continue to invite back stakeholders and course-correct to make sure that the measures that we’re putting in place and the approaches that we’re taking are actually reflective of what the needs of that community are.

We need to put the human at the center.

Victoria: What advice do you give people for being an ally, when there is a risk to themselves? I think there are a lot of people who want to do something, but they’re not sure what to do, or they’re scared to do something.

Danielle: I’d like to remove the shame from that, first of all. You shouldn’t feel guilty — people should feel comfortable taking care of themselves. All of us even leading up to today’s event are asking what kind of personal risk are we facing and what kind of challenges, how do we support those we care about, but also how do we consider our own self care?

And I want people to not feel pressured. Sometimes you don’t have the power to do everything you want to do. It’s okay. I want to lay that out as an option. If you do have the opportunity to take personal risk and support someone you care about, we celebrate and appreciate it. But I want to say it’s not always the only supportive way to act. Sometimes you have to protect yourself for a future day where you’ll have a different opportunity or a different power.

Katlyn: I would also challenge people to think about their positionality very critically in different interactions. It is important to find a balance of keeping yourself safe, but also thinking about the spaces where you’re able to move the needle a little bit in an ongoing way, every single day. That is a very important practice for those of us who want to work towards being anti-racist and intersectional in our daily lives.

It’s not enough to read a book. Sometimes you’re in a room where you’re the only woman in that room. Or you’re the only person of color in that room. Or you’re the only person of your intersectional identity that is aware of certain issues. So I would challenge and encourage people to think about making an impact in every situation when they can.

Projects of hope: channeling darkness into productive outlets

Victoria: Finally, we’re coming out of a pretty dark year and a half. I’d like to know what you’re each working on right now that gives you hope for the future?

Catherine: Some of the work that’s happening in my lab, where we’re working on a collaborative project with partners in Latin America called Data Against Feminicide which focuses on gender-based violence and building both networked relationships and technologies to combat it. In other words, technical and social infrastructure for activists who are collecting counterdata to try to hold institutions accountable for this violence.

I am so inspired by the care that they bring to that work and the diverse ways that they’re seeking justice for these women that have been killed. They’re seeking the restoration of their memory as people. That kind of work gives me great hope for what can be accomplished.

Katlyn: I will highlight one project called Invisible Variables and it’s part of a decision support tool that Danielle and I, and a bunch of collaborators have been developing to support municipal decision-making due to disasters. Right now that means focusing on COVID. And it’s basically asking people all over greater Boston through interviews how their life has been impacted by the pandemic and by social distancing mandates. We’re specifically aiming to ask from an intersectional feminist perspective of focusing on things like your safety, your financial security, your autonomy, and sort of the self-determination and the interplay of those factors in areas like housing and employment.

I feel hopeful thinking about that project because the data that we’re getting and the stories that we’re getting, I hope will lead to prioritizing equity at a municipal level.

Danielle: At Space Enabled where Dr. Turner and I work, we ask how we can advance justice in Earth’s complex systems using designs enabled by space.

Sometimes it’s by using interviews to understand that people are affected by public services and changes in public policy. We’re also doing things that sound quite different. Like we’re trying to invent the use of wax as a fuel for satellites. But at the same time, we’re also asking how to reduce the space debris. We are co-leading a project on space debris reduction with an international team of collaborators.

What’s exciting is that the foundation of why I do these projects is still rooted in feminist and anti-colonial thinking combined with an appreciation for recovering from oppression that has been such a strong pattern in our world for the last 500 years. I teach a class in fall semesters where people can learn more about this.

It’s called “Can Space Enabled Design Advanced Justice and Development”? We basically spend the first third of the class reading discouraging and disturbing history about slavery and colonization and harm for people from different backgrounds. Then we ask the question: what if as engineers, designers, and architects, we use systems thinking to be very aware of history when we’re designing? Dr. Turner and I propose a framework that seeks to help us solve problems by asking: can we be anti-racist, feminist, queer-friendly, and anti-colonial at all times during the design of complex systems?

I’m really thankful to be in a place where I feel it’s academically safe to do that — meaning I think I can pursue tenure doing this, which is very exciting. And that’s unique. I appreciate that the MIT Media Lab is a place where we can explore that.

Abhishek: I’m feeling hopeful about 3 big projects.

The first is the AI Ethics Learning Community — we have a cohort that’s running right now with weekly discussions that anyone can sign up to watch.

We also have our newsletter called The AI Ethics Brief that goes out to 5000 people every week.

And finally, I have a book coming out this summer called Actionable AI Ethics about translating all of these ideas from principles to practice.