🔬 Research Summary by Stephan Schlögl, a professor of Human-Centered Computing at MCI – The Entrepreneurial School in Innsbruck (Austria), where his research and teaching particularly focuses on humans’ interactions with different forms of artificial intelligence tools and technologies.

[Original paper by Anna Stock, Stephan Schlögl, and Aleksander Groth]

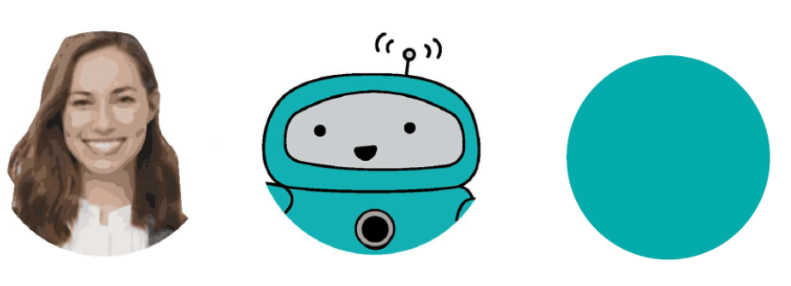

Overview: Self-disclosure and respective personal reflections are crucial for mental health care and wellbeing. Here, chatbots may be considered a low-threshold tool to facilitate such interactive information sharing, where studies have indicated that people may disclose even more to chatbots than to other humans. We wanted to explore this and understand how the type of chatbot appearance, i.e., a basic human-like appearance via a stylized photo vs. a robot-like appearance vs. a none-embodied appearance, can affect people’s self-disclosure behavior.

Introduction

Chatbots have also seen an increasing uptake with the rise of voice-based conversational assistants such as Google Siri and Amazon Alexa. Particularly in the health and wellbeing domain, these AI-powered social companions have gained traction, offering support in mental health through psycho-education, information access, and even basic therapy. Their 24/7 availability and low entry barrier make them valuable – especially when trying to reach individuals who are more reluctant to seek traditional therapy due to cost or stigma. As chatbots can come in many shapes and forms, our goal was to better understand their appearance’s effects on interlocutors’ information exchange behavior, i.e., people interacting with them. We used an online experiment in which we asked three groups of people to interact with a chatbot. For each group, the chatbot used a different appearance: (1) a small stylized photo of a woman, (2) a robot pictorial, and (3) a filled circle (i.e., there was no actual embodiment). We found that the human-like embodiment positively affected people’s self-disclosure behavior, showing greater breadth and depth in the provided information.

Key Insights

Whether text-based, pictorial, or animated, today’s chatbots may be considered media agents, eliciting different types of social reactions and triggering information-sharing behavior in the people they engage with. To this end, previous research has shown that the level of anthropomorphism, i.e., the degree to which the visual representation of an artificial entity resembles the looks of a human, significantly affects these interactions and respective information-sharing behavior. However, two somewhat conflicting theories exist in which direction this influence goes. On the one hand, it has been argued that people would disclose less to chatbots that show human resemblance since they may be afraid of being exposed to similar social risks as when communicating directly with another human being. On the other hand, communication theory holds that exposure to a human face may actually help in encouraging information disclosure, as it can offer an initial starting point based on which a much deeper social connection may be established. Our goal was to study these contrasting views and thereby shed more light on a chatbot’s visual representation’s impact on individuals’ information disclosure behavior.

Study Design and Analysis

To study self-disclosure in chatbot interactions, we compared three different chatbot designs with varying levels of human resemblance (cf. figure below). We used a between-group experimental design in which group 1 was exposed to a human-like chatbot appearance, achieved via the stylized photo of a woman, group 2 was confronted with a more technical appearance expressed by a robot pictorial, and group 3 acted as a control group for which the chatbot was simply represented by a filled circle. Each of the n=178 experiment participants was randomly assigned to one of these groups and then asked to interact with their respective chatbot.

In these interactions, we asked participants to answer different questions, disclosing information at different sensitivity levels. We used demographic questions to gather information on participants’ backgrounds, perceptive questions to assess how participants perceived the human likeness of the chatbot designs, and informative questions to explore participants’ information disclosure behavior. Of course, all of these questions were optional, allowing participants to choose whether or not to provide answers. Subsequently, we analyzed people’s answers concerning their breadth (number of words) and depth (according to the OID analysis scheme).

Findings

Our results show that disclosure to the chatbot with human resemblance (i.e., the stylized photo used for group 1) was greater than with robotic resemblance (group 2) or without embodiment (group 3). Regarding the depth of answers provided by participants, it was evident that the human-like chatbot elicited more detailed and comprehensive responses, particularly when participants were asked about their greatest fears. These responses contained richer content than those generated by the robot-like chatbot and those generated by the none-embodied chatbot.

Another consistent pattern emerged when examining the breadth of answers in terms of the number of words used. Once again, the question about people’s greatest fear stood out, as participants interacting with the human-like chatbot provided significantly longer responses than those engaging with the robot-like chatbot or the non-embodied chatbot. This suggests that the human-like representation encouraged participants to elaborate on their answers to this question.

Furthermore, looking at answer behavior, it became evident that the robot-like chatbot representation had a higher incidence of missing or elusive answers to questions. A notable 15.15% of participants interacting with the robot-like chatbot left at least one question unanswered or provided non-substantive responses. In contrast, only 11.54% of participants interacting with the none-embodied chatbot and 10.00% of participants interacting with the human-like chatbot exhibited similar behavior, indicating a lower rate of missing or evasive answers.

In summary, our data supports the assumption that the human-like chatbot was more effective in prompting more detailed and expansive responses, particularly regarding questions regarding people’s greatest fears. Conversely, the robot-like chatbot had a higher incidence of missing or vague answers than the other representations.

Between the lines

Although our findings are interesting, they hold a number of notable limitations. First, unlike previous studies with digital assistants such as Alexa and Siri, our study focused on text-only interactions, which may have influenced disclosure behavior. Second, participants answered questions in a private, unsupervised setting, making them more open to disclosure. Third, the static nature of the human-like representation may have reduced the so-called uncanny valley effect, which in previous studies triggered feelings of eeriness in cases where the human-like appearance was too good and thus negatively affected disclosure. In summary, our research results helped shed more light on one small aspect of the complex relationship between chatbot appearance and information disclosure. Additional long-term studies, however, are needed to confirm our findings and further evaluate the effects of confounding factors.