✍️ By Jim Huang, Solutions Director and AI Ethics Researcher, and Abhishek Gupta, Founder and Principal Researcher, Montreal AI Ethics Institute.

Editor’s Note: This article, ‘“Made by Humans” Still Matters’ was initially drafted by Jim Huang and the late Abhishek Gupta in December 2022.

At the time, AI-enabled image generators were still in their early stages, with the original Stable Diffusion first released in August 2022, followed by Stable Diffusion 2.0 in November 2022. Stable Diffusion 3 Medium was released in July 2024, followed by Stable Diffusion 3.5 in October 2024, which, as of January 2025, remains the most recent stable release. Similarly, DALL-E 2 entered beta in July 2022 before becoming widely available in September 2022 and was later succeeded by DALL-E 3 in October 2023.

The insights in this article reflect the state of AI and its societal implications as understood at that time. However, with the rapid evolution of multimodal generative AI—spanning text, images, video, voice, and music—these discussions are more relevant than ever. For further exploration, see “AI Art and its Impact on Artists” (AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (AIES ’23)).

Overview: For the past few years, creative communities have been experiencing increasingly heightened anxiety about AI-enabled image generators like DALL-E and Stable Diffusion advancing to the point of replacing human artists. Using short text prompts, generative AI can produce novel and genuinely creative digital artwork in seconds.

Whenever innovative technology brings about a cultural shift, affected communities are left in a state of purgatory, unsure of where they fit and how to adapt, especially when the technology threatens livelihoods. In times of uncertainty, we need guidance on how automation will take over and where the “Made by Humans” brand still matters.

Generative AI will transform how some art is produced, but not all of it

Image generators, such as DALL-E and Stable Diffusion, have advanced to the point where producing quality visual art with Artificial Intelligence (AI) is not only possible but fast and virtually cost-free. Currently, anyone can input descriptive text in the form of a prompt to a Generative AI (GenAI) program, and it can ostensibly output creative art in seconds.

In the past few years, GenAI has been heightening artists’ anxieties across various art communities, from graphic designers to forensic sketch artists. These creative communities worry about how this new technology will affect them, from losing a part of their livelihoods to being made outright redundant in the worst-case scenario. In times of uncertainty, we need sober and actionable guidance on what we can do.

The Appeal of Art

What makes a work of art attractive can vary greatly from person to person. The feelings that arise from taking in art can often be nebulous and indescribable. On top of a work’s visual appeal, some may care immensely about its uniqueness and the story behind the original piece. Others may not care at all if the work is a reproduction.

Some order Picasso posters from Amazon, while others prefer buying original pieces from art dealers. Some shop for mass-produced jewelry, while others prefer visiting artisanal stores for bespoke designs. Artisanal and human-made works will always have a place in society and carry an appeal beyond the actual look of the work. A consumer who enjoys human-made art may care that the work took time and effort. They may enjoy learning about the story behind the piece, the production process, and the commentary that it makes about the state of our society. Socially, they may also enjoy the community surrounding the art and their relationship with the artist. This is difficult to emulate with AI-generated art because it misses the distinctly human element.

“Made by Humans” Art

Some artists may consider more commercial roles, like advertisement design, as their primary creative calling, while others only take on these jobs to supplement their income as they pursue other aspirations. Regardless, GenAI’s ability to quickly produce commercial art will affect both types of artists, impacting their ability to earn a livelihood and continue producing art. It goes without saying that a society that can express itself artistically is an inherent good, and any paradigm shift, cultural, political, or technological, that threatens the production of beautiful, meaningful works becomes a major societal issue.

There are some ways to protect these roles. One way would be to normalize transparency and the promotion of human artists behind all forms of art, including designs such as those on book covers or billboards. Another way would be to increase funding for art foundations and grants. Policymakers can invest more in organizations supporting human artists to balance out the negative effects of GenAI. Individual citizens can also donate and become patrons of the artists they personally admire. However, this can only happen if we can first identify and differentiate works that are “Made by Humans.” Having a “Made by Humans” label ensures consumers may trust that the production of art requires the effort of human craftsmanship.

We may learn from the successes and pitfalls of other labels applied to products, such as “Organic” or “Eco-Friendly” categorizations. One issue comes in the form of non-organic or non-eco-friendly goods still using the label anyway. To combat this, an independent governing body could be actioned to evaluate and enforce rules on what is considered “Made by Humans.” However, a major problem that may stem from this solution is if the “Made by Humans” label becomes a paid certification for creators. This adds an unnecessary monetary barrier to entry for artists wishing to prove that they are human, a uniquely dystopian thought.

Practically, it may be easier to require all GenAI programs or social media platforms to label AI-generated work as “Made by AI” instead, such as the case currently with Instagram. However, we find that there’s a crucial difference between encouraging art “Made by Humans” and discouraging art “Made by AI.” Society ought to deliberately and positively value human-made art. In addition, it is easier for opportunistic creators to omit the “Made by AI” label than dishonestly applying a “Made by Humans” label.

Invariably, there will be cases that blur the line between how much a work of art can be automated while still being considered human-made. Everyone agrees that a painting produced by a person with a physical brush and acrylics is considered human-made. However, there may be debate surrounding artists using a digital brush that automatically adds texture and designs to an outline. Our emphasis here is not to provide the perfect solution on how to label but to elevate the importance of humanity in the creative process and to lean into that as a differentiating factor for artists with the emergence of GenAI.

A Sense of Community

We produce art as a way to express ourselves. Even though GenAI can produce art indistinguishable from human works, there’s a sterile feeling when imagining a world of art made solely by machines. Art is not only a collection of aesthetic brushstrokes but a reflection of the deep emotions placed into it and the story of the artist who made it. Although, as viewers, we may not feel the exact emotions of the artist when they created their works, we can infer and empathize with what they have been through when we learn of their life’s story. This happens because, as humans, we share mental models and experiences with fellow human artists that allow us to empathize in a way that machines just can’t. Stuart Russell, in his book Human-Compatible, makes the case for why machines, in their present standard model, fail to achieve some of the preference realizations that humans care about precisely because they lack a shared basis with us, the humans.

Spanish romantic painter Francisco Goya created his series of Black Paintings in the later years of his life, works that were drastically different from his early paintings. Experiencing the horrors of the Napoleonic Wars, the civil strife that came afterwards, and suffering from several life-threatening illnesses, Goya went on to create a body of haunting and bleak works that reflected his mental state at the time, the most famous being Saturn Devouring his Son. We can feel Goya’s desperation and anxiety when we gaze upon the painting. This is amplified by our knowledge of Goya’s suffering during his turbulent times, and this shared basis provides us with a model to imbue the piece of art with extra meaning. If a similar work were to be produced by a machine, it would lack the same backstory, emotion, and meaning because we have limited ways to peer into its “alien intelligence” and understand why it made certain choices over others.

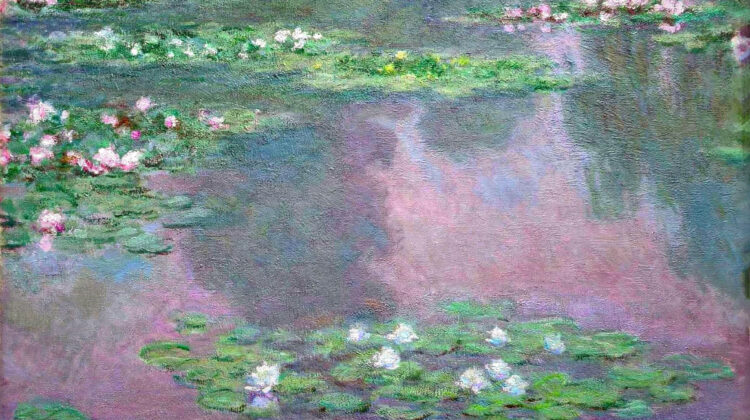

French Impressionist painter Claude Monet produced most of his Water Lilies series while suffering from cataracts. The oil paintings of his flower garden and pond reflected how he saw the world. Through his eyes, the colours of his water lilies look faded, with blurry halos appearing around light sources, producing a soft, dreamlike aesthetic to his works. Gazing upon his work, we may consider the inner feelings of a painter struggling with failing eyesight.

Ultimately, GenAI is here to stay, but that doesn’t mean we have to accept a world devoid of human art. In fact, if we adapt our policies and outlook responsibly, GenAI can serve as a counterpoint to emphasize human-made art and even give us inspiration for a wider world of fresh, exciting art.

Only time will tell how GenAI will impact creative communities, but we can’t sit idly by and let the technology run its course. Our best chance at a positive outcome is to continue the discourse on GenAI and proactively develop guidelines on how to treat AI-generated art so that we may gain convenience and inspiration from AI while still cultivating and celebrating human-made art.