🔬 Research Summary by Alice Qian Zhang, a computer science major at the University of Minnesota interested in content moderation, mental health, and responsible artificial intelligence.

[Original paper by Alice Qian Zhang, Kaitlin Montague, and Shagun Jhaver]

Overview: Flagging is the primary way social media users can report inappropriate content they counter to remove it from the site. This paper examines the affordances and practices of flagging from the perspective of social media users experienced in flagging content on platforms such as Facebook, Twitter (X), and Instagram. Our analysis offers suggestions for enhancing transparency and safeguarding user privacy within the flagging design space to harness its potential for better serving end-users reporting needs.

Introduction

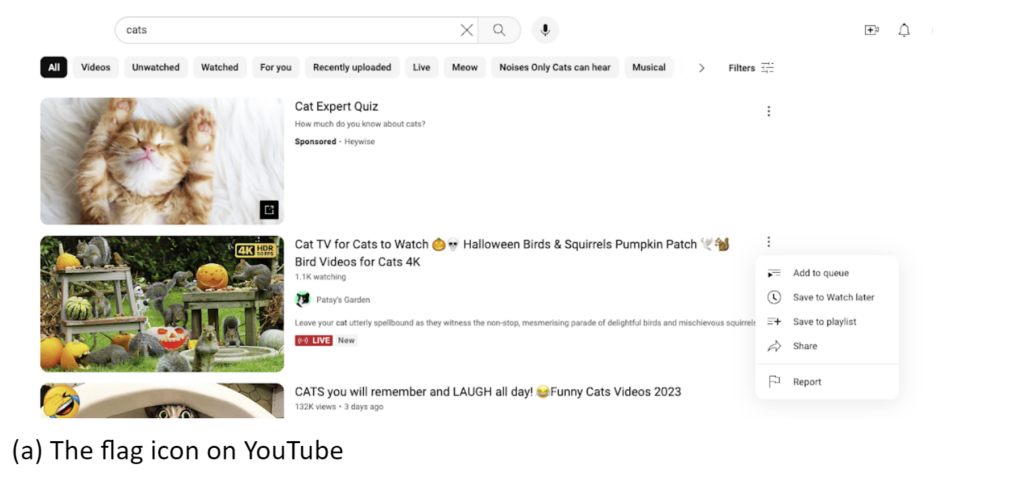

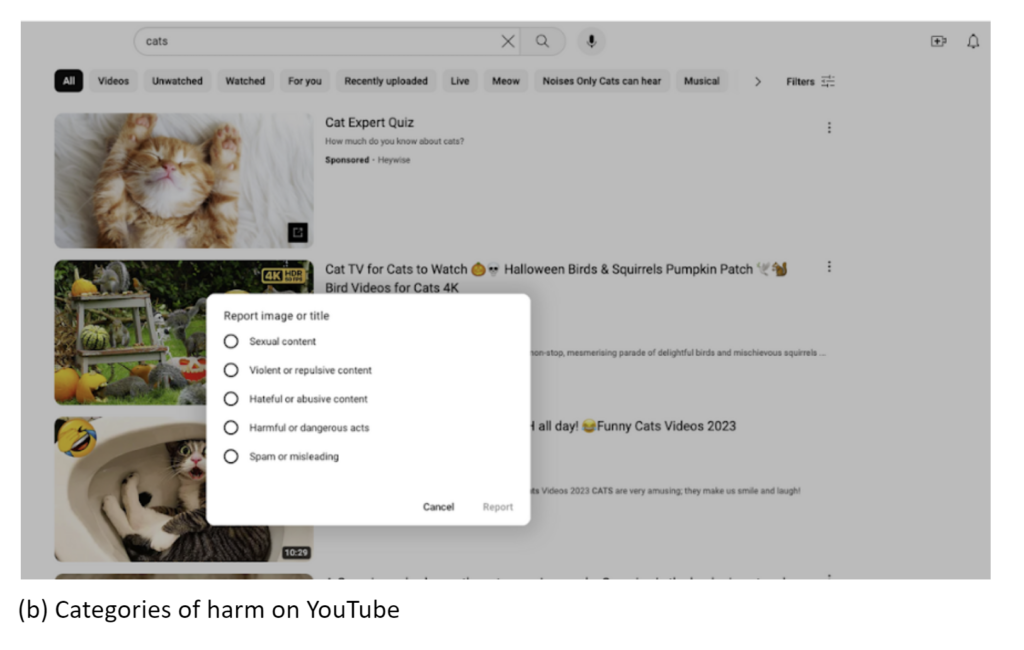

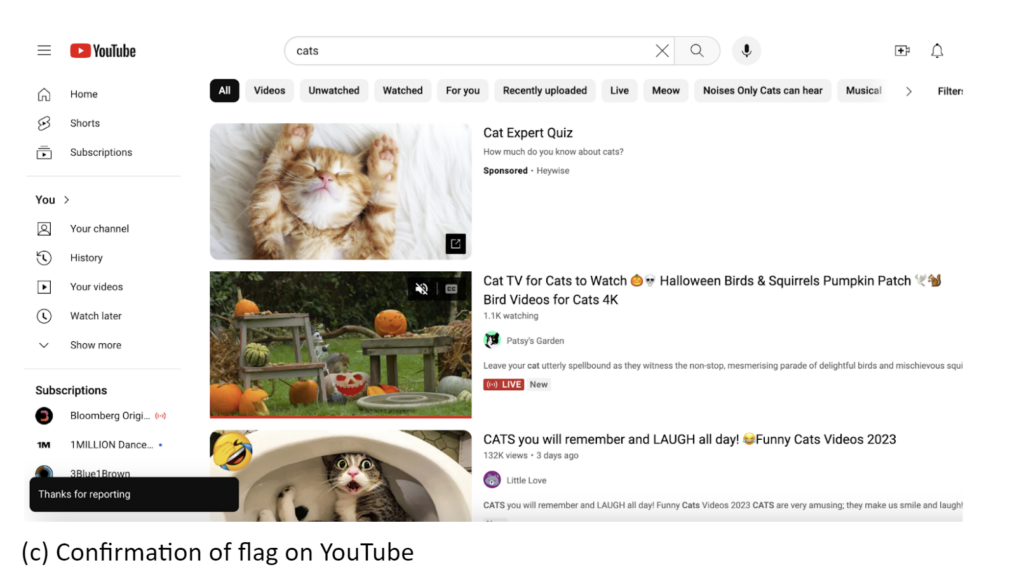

How do social media platform users provide feedback to platforms when they view harmful content? Despite the ever-changing nature of online platforms, the mechanisms by which users can report inappropriate content have remained relatively limited and unchanged over the past three decades. Flagging is the primary action users can take to report content they believe violates platform guidelines. Flags are often presented as icons users can click to report or “flag” harmful content. Most social media platforms offer guidelines on what constitutes harmful content, often termed “community guidelines.” These guidelines cover many of the well-known categories of harm, such as sexual content, violent content, harassment, misinformation, spam, and more. However, it is often unclear to users when to engage in flagging or what occurs when they decide to flag content. For example, Figures (a) through (c) showcase the flagging process on YouTube, during which the only feedback users receive for flagging content is a “Thanks for reporting” message. Note that while we call these mechanisms “flags” in our research, many platforms use other terms, such as “report,” to refer to the same mechanisms.

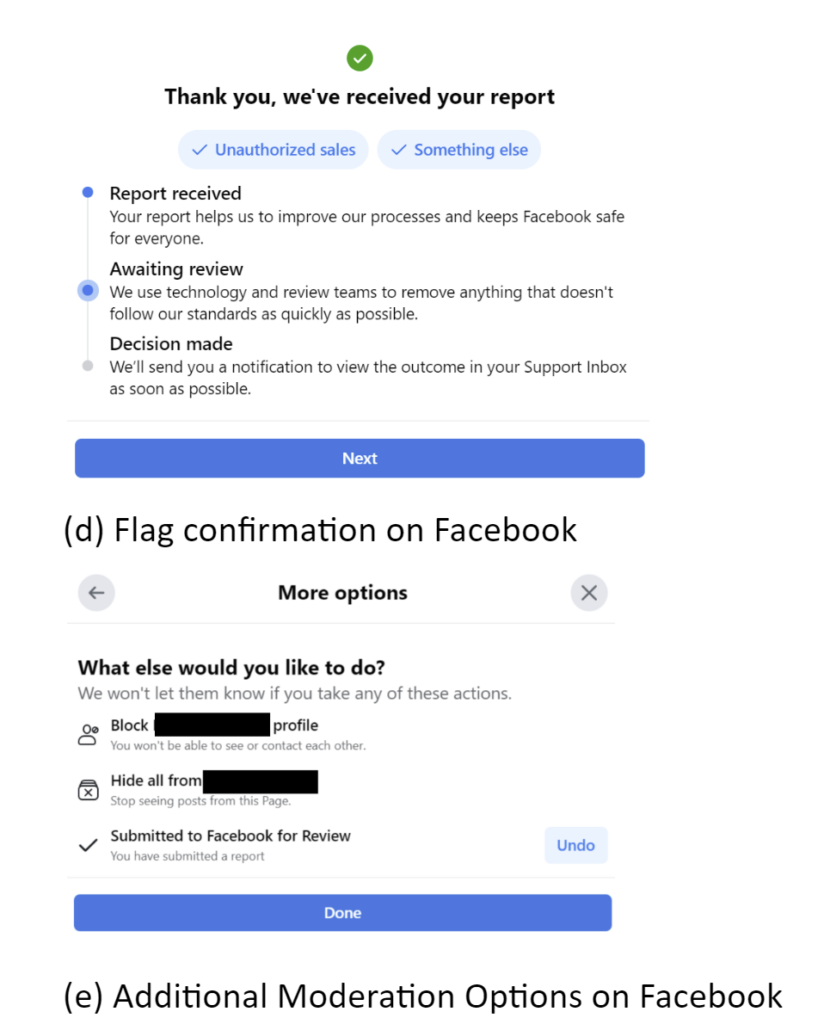

In contrast, Figures (d) through (e) show how Facebook prompts users to take further action when they flag a post, such as asking if they want to block the account that posted the harmful content or hide all of their posts. In this way, Facebook’s more sophisticated flagging process allows users to incorporate other moderation tools, such as blocking and hiding content, to further protect themselves from harmful content.

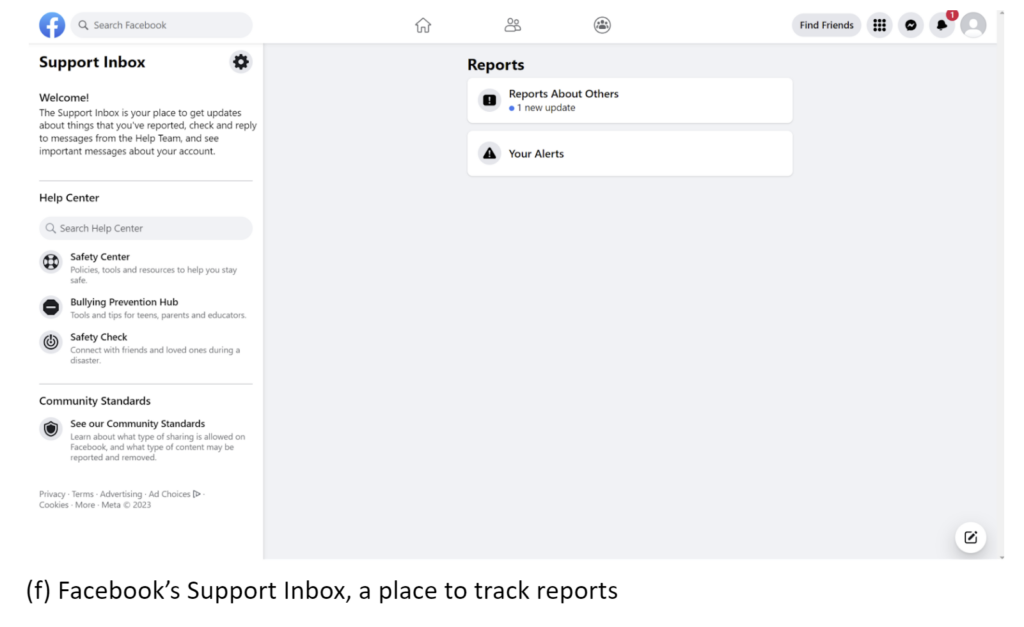

Figures (f) and (g) show Facebook’s Support Inbox, an interface that allows users to track what happens to the content they report. In contrast to YouTube, which provides only a thank you message, Facebook’s model offers users a separate interface dedicated to tracking the status of their flags. These two examples show that even among major social media platforms such as Facebook and YouTube, there are discrepancies in how platforms approach flagging. This, in turn, may affect how platform users choose to engage in flagging.

To understand flagging from platform users’ perspectives, we interviewed 22 active social media users who recently reported content to understand their perspectives on flagging procedures. These factors motivate or demotivate them to report inappropriate posts and their emotional, cognitive, and privacy concerns regarding flagging. Our analysis of this interview data shows that a belief in generalized reciprocity motivates flag submissions. Still, deficiencies in procedural transparency create gaps in users’ mental models of how platforms process flags. We highlight how flags raise questions about distributing labor and responsibility between platforms and users for addressing online harm. We recommend innovations in the flagging design space that provide greater transparency about what happens to flagged content and how platforms can meet users’ privacy and security expectations.

Key Insights

Flagging as Part of a System of Moderation Tools

As in the example of Facebook above, we surfaced an understanding that flagging is a key part of a system of moderation tools. Our interview participants used additional tools like blocking to protect themselves from further exposure to harmful content. However, through our analysis, we learned that while participants blocked content to protect themselves, they flagged content to protect others, such as their friends, family, and children, from harm. This motivation often derives from a sentiment of generalized reciprocity in which users flag inappropriate posts to protect others and expect the same in return, believing that these actions would collectively result in healthier online spaces.

While our participants were intrinsically motivated to flag content, we also surfaced tensions around how flagging is perceived. For example, while many of our participants viewed flagging as a right they had on platforms, they balked at the idea of flagging as an obligation rather than a choice. One reason for this was the knowledge that users’ flagging actions are unpaid by platforms. These participants thus reasoned that platforms should always offer users a choice to flag, but it should remain a voluntary action for users to engage in.

Incorporating Transparency in Flagging

In support of much prior literature on the importance of transparency in moderation procedures, such as informing users about why their posts are removed, our analysis shows that transparency is crucial in flagging procedures. Platforms become responsible for following up with flags by providing flagging procedures to users. Failing to explain why the content they flagged was removed or kept on a platform can frustrate the users. Even more damaging is how this lack of transparency and feedback prevents users from accurately understanding flag processing, instead leaving them in the dark. Some of our participants concluded that flagging is simply a “smokescreen” with no platform functionality or support. These participants stopped flagging once they came to this realization. Such disillusion about the utility of flagging can, over the long term, exacerbate the potency of online harms.

Another concern is that social media users may be unaware of flags or their value in addressing online harms without explicit encouragement from those around them or the platform’s educational initiatives. We found that though flagging itself is confined to the interface of the social media platform, several of our participants learned that they could flag content online through face-to-face interactions at school or with friends. To increase digital literacy about addressing online harms, schools, education leaders, media sources, and content creators should promote an understanding of flags and other safety mechanisms on social media. Platforms may also build rapport with these stakeholders by providing resources to support educational initiatives for flagging.

Implications for Designing Flagging Mechanisms

Building on our questions above, we investigated participants’ reactions to potential changes to flagging interfaces. We asked whether flags from certain individuals, such as influencers, should be prioritized over flags by ordinary platform users or if certain types of content should be prioritized when flagged (e.g., death threats). Though participant responses were mixed, a key design recommendation participants keenly supported was that regardless of how platforms prioritize their flags, they should be transparent about the reasoning behind their prioritization.

We also probed participants’ views on a scenario where all other platform users could see when a post or an account was flagged. However, participants raised concerns about safety with these hypothetical changes. There is a fear that when reporting an account responsible for enacting harm online, users may subject themselves to direct attacks from that account or its supporters. A lack of guidance from platforms about when to use different feedback mechanisms may also cause platform users to adopt the flag as a “dislike” button. This may water down the flag’s purpose, which is a serious method of reporting concerns with harmful content. To balance the need for privacy and transparency, we suggest that designers explore the tradeoffs of solutions in this space, such as providing a count of the number of flags on each content.

Lastly, we find a rich design space in which designers can improve flagging procedures to address the specialized needs of individuals from marginalized communities. In line with prior work, our participants were concerned that such individuals not only get frequently falsely flagged but often face a greater burden of reporting inappropriate content. We suggest that platforms employ design methods to collaboratively improve flagging procedures with these communities to address their needs better.

Between the lines

Ultimately, our analysis provides a unique view of flagging from the perspective of platform users who are often left in the dark about its procedures. We find that users perceive flags not as a stop-gap solution compensating for platforms’ limited moderation resources but as an essential avenue to voice their disagreements with curated content. Our participants’ willingness to contribute their time, even going so far as personally contacting the people who post content they flag to take it down, shows users’ investment in addressing online harms. Our analysis shows that flagging serves as an act of generalized reciprocity for users. However, we found that a lack of procedural transparency in flagging implementations undermines users’ trust. Many questions remain unanswered about how to design flagging interfaces optimally or what role other stakeholders, such as flagged users, moderators, and bots, play. We call for researchers to investigate these questions and examine flags as part of an ecology of communication tools individuals use to address online harm.