✍️ Column by Jeff Sebo and Leonie N. Bossert

Jeff Sebo is Clinical Associate Professor of Environmental Studies, Affiliated Professor of Bioethics, Medical Ethics, Philosophy, and Law, Director of the Animal Studies M.A. Program, Director of the Mind, Ethics, and Policy Program, and Co-Director of the Wild Animal Welfare Program at New York University. His latest book is Saving Animals, Saving Ourselves.

Leonie N. Bossert is Assistant Professor at the International Center for Ethics in the Sciences and Humanities at Tübingen University with a research focus on sustainable AI, animal and environmental ethics. Her latest book is Common Future for Humans and Animals – Animals in Sustainable Development (published in German).

Overview: This column discusses the ethical implications of creating artificial animals to replace real animals in captivity for entertainment and education. While this technology could reduce the suffering of biological animals in captivity, artificial animals may undermine the purpose of zoos and soon become sentient beings themselves capable of being harmed. The authors conclude we should pursue this technology cautiously, limiting risks like moral uncertainty, and not view artificial animals as an adequate replacement for phasing out zoos and aquariums.

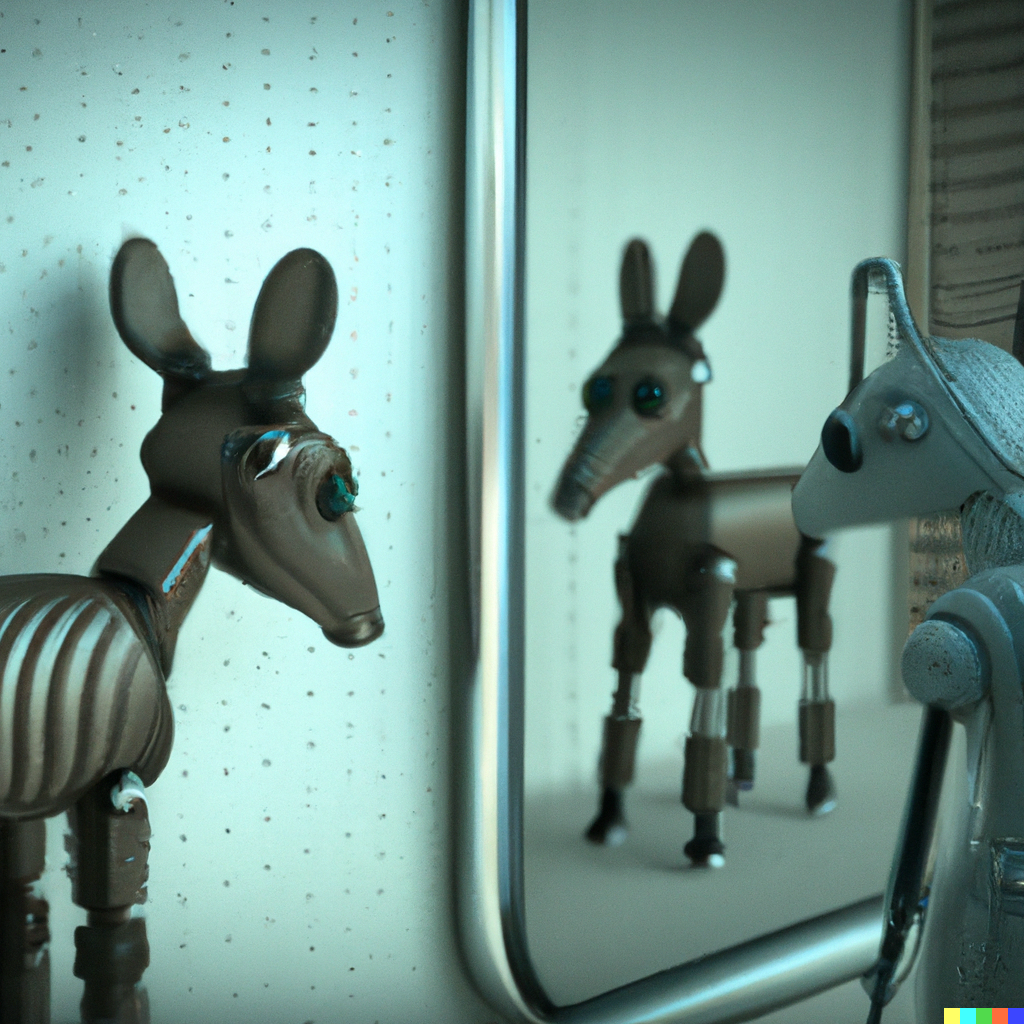

Imagine watching a dolphin swim in a marine park while a human audience cheers. In the past, you felt uncomfortable watching captive wild animals perform for humans since you worried that this kind of entertainment harmed the animals. But in this case, you feel differently since this dolphin is not an animal at all – or at least, not a biological one. Instead, this dolphin is a robot.

The California company Edge Innovations is developing artificial animals by blending “live puppeteering, programmed behavior, and artificial intelligence” to “reimagine the entertainment, educational, and business potential of the marine animal industry.” Essentially, this technology will allow humans to interact with animals without keeping biological animals in captivity as a means to that end.

Many humans, including animal advocates, celebrate this development as a victory for humans and nonhumans. The hope is that in the same way that we can use technologies like plant-based and cultivated meat to replace our current use of animals for food, we can also use technologies like robotic and simulated animals to replace our current use of animals for entertainment.

However, as with any new technology, artificial animals raise various ethical questions. For example: Is this new technology scalable and sustainable? And is there a risk that replacing biological animals with artificial counterparts will make zoos and aquariums appear more humane than they really are, thereby providing ethical cover for their continued use of other biological animals?

These questions are important; we expect the answers to provide grounds for caution about creating artificial animals. But we want to focus here on two other related ethical questions. First, do artificial animals undermine the purpose of zoos and aquariums? And second, can artificial animals themselves be harmed or wronged in the same kind of way that biological animals can be?

Consider the purpose of zoos and aquariums. The practice of keeping wild animals in captivity calls for a defense, and a common defense is that zoos, aquariums, and other such institutions support research, conservation, education, and entertainment. Whether or not this defense is adequate, it might help to ask whether and to what extent artificial animals help zoos and aquariums achieve these goals.

Many experts have argued that zoos and aquariums struggle to achieve their educational goals even with biological wild animals. When you study a wild animal in captivity, you learn what this animal is like in captivity, but this is different from what the animal is like in the wild. (You might also learn that using this animal for entertainment is acceptable, which might be a bad lesson to learn.)

If we replace biological animals with artificial counterparts, will these problems persist? Possibly. If we program artificial animals to behave like wild animals in captivity, we risk learning the same bad lessons as before. And if we program them to behave like wild animals in the wild, we risk learning a new bad lesson: that wild animals have better prospects for flourishing in captivity than they do.

Of course, a lot depends on human psychology. Will humans naturally psychologically associate biological and artificial animals? To the extent that the answer is yes, the educational benefits might be higher, but the educational risks will be higher, too. Otherwise, the educational risks might be lower, but the educational benefits will be lower, too. Either way, the educational possibilities appear limited.

And, of course, whether or not keeping biological animals in captivity advances research and conservation goals, keeping artificial animals in captivity will have limited use for these purposes. This leaves entertainment as the primary expected benefit of this technology. So when we ethically assess this technology, the primary question is: Is the benefit of entertainment worth the various risks?

This brings us to our second question, which is whether artificial animals can, themselves, be harmed or wronged. After all, the point of replacing biological animals with artificial counterparts is that captivity and control can be bad for biological animals. If we discover that captivity and control can be bad for artificial animals, too, that might undermine this solution to the problem.

So, what does it take to be the kind of being who can be harmed and wronged? Philosophers continue to debate this question, but the most common answers are that sentient beings (beings who can feel) can be harmed and wronged, and sapient beings (beings who can think) can be harmed and wronged. Might artificial animals count as sentient or sapient, either at present or in the future?

At present, artificial animals are almost certainly not sentient or sapient. They might be capable of feeling and thinking in a general sense of these terms since they can convert perceptual inputs to behavioral outputs in seemingly intelligent ways. But they almost certainly lack these capacities in a more specific sense of these terms since there is almost nothing that it is like to be these animals right now.

However, this technology is advancing rapidly. Advances in robotics are happening alongside advances in artificial intelligence (AI), with Google, Microsoft, and other companies developing AI systems that can approximate human-level performance on various tasks. With each passing month, the difference between biological and artificial cognition and behavior is shrinking, and this trend will likely continue.

We can easily imagine a future where humans combine these technologies to produce strikingly realistic artificial human or nonhuman animals with integrated and embodied capacities for perception, learning, memory, anticipation, self-awareness, social awareness, communication, and rationality. At that point, it will no longer be clear that these beings cannot be harmed or wronged.

This amplifies the risks involved with this new technology. Keeping biological animals in captivity for research, conservation, education, and entertainment can be problematic. But if artificial animals might be unscalable and unsustainable, have limited value for research, conservation, and education, and soon have unclear moral status, we should also be cautious about using them.

Granted, many new technologies are worth pursuing despite the risks. For example, cultivated meat (meat that comes from a cell culture) may or may not be scalable and sustainable, and it may or may not reinforce the harmful idea that flesh is food. Yet many animal and environmental advocates support pursuing this technology anyway since they think the potential benefits outweigh the risks.

However, the difference is that the potential benefits of artificial animals are lower, and the risks are higher. The world needs a viable meat alternative, but not a viable captive animal alternative. A mature meat alternative will not have unclear moral status, but a mature captive animal alternative will. So, it can be reasonable to hold that the potential benefits outweigh the risks in one case but not the other.

Does this mean we should reject artificial animals entirely? No, but it does mean we should install guardrails. Ideally, we would avoid creating beings with unclear moral status, and if we did create such beings, we would err on the side of extending their moral standing. That would allow us to enjoy this technology while preventing or, at least, preparing for problems that might arise.

However we solve these problems, we should start laying the groundwork for the solutions now. Technological progress is much faster than social, legal, and political progress. While we might not have a multispecies Westworld yet, we might be capable of having one soon. And if we want to mitigate the damage, we need to start thinking seriously about the moral, legal, and political limits now.